Spider

With a few striking exceptions, the true spiders of Ceylon resemble in oeconomy and appearance those we are accustomed to see at home;—they frequent the houses, the gardens, the rocks and the stems of trees, and along the sunny paths, where the forest meets the open country, the Epeira and her congeners, the true net-weaving spiders, extend their lacework, the grace of the designs being even less attractive than the beauty of the creatures that elaborate them.

Such of them as live in the woods select with singular sagacity the bridle-paths and narrow passages for expanding their nets; perceiving no doubt that the larger insects frequent these openings for facility of movement through the jungle; and that the smaller ones are carried towards them by currents of air. Their nets are stretched across the path from four to eight feet above the ground, suspended from projecting shoots, and attached, if possible, to thorny shrubs; and they sometimes exhibit the most remarkable scenes of carnage and destruction. I have taken down a ball as large as a man's head consisting of successive layers rolled together, in the heart of which was the original den of the family, [pg 465] whilst the envelope was formed, sheet after sheet, by coils of the old web filled with the wings and limbs of insects of all descriptions, from large moths and butterflies to mosquitoes and minute coleoptera. Each layer appeared to have been originally hung across the passage to intercept the expected prey; and, when it had become surcharged with carcases, to have been loosened, tossed over by the wind or its own weight, and wrapped round the nucleus in the centre, the spider replacing it by a fresh sheet, to be in turn detached and added to the mass within.

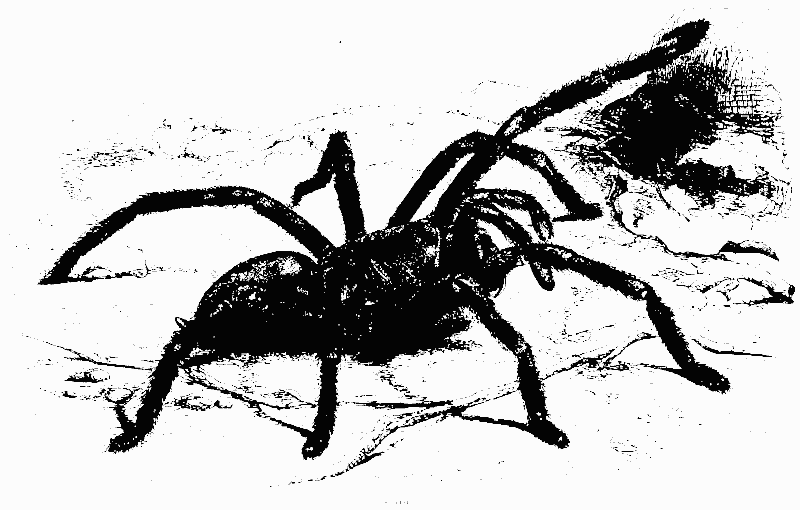

Separated by marked peculiarities both of structure and instinct, from the spiders which live in the open air, and busy themselves in providing food during the day, the Mygale fasciata is not only sluggish in its habits, but disgusting in its form and dimensions. Its colour is a gloomy brown, interrupted by irregular blotches and faint bands (whence its trivial name); it is sparingly sprinkled with hairs, and its limbs, when expanded, stretch over an area of six to eight inches in diameter. It is familiar to Europeans in Ceylon, who have given it the name, and ascribed to it the fabulous propensities, of the Tarentula. 1

The Mygale is found abundantly in the northern and eastern parts of the island, and occasionally in dark unfrequented apartments in the western province; but its inclinations are solitary, and it shuns the busy traffic of towns.

The largest specimens I have seen were at Gampola in the vicinity of Kandy, and one taken in the store-room [pg 466] of the rest-house there, nearly covered with its legs an ordinary-sized breakfast plate. 2

This hideous creature does not weave a broad web or spin a net like other spiders, but nevertheless it forms a comfortable mansion in the wall of a neglected building, the hollow of a tree, or under the eave of an overhanging stone. This it lines throughout with a tapestry of silk of a tubular form; and of a texture so exquisitely fine and closely woven, that no moisture can penetrate it. The extremity of the tube is carried out to the entrance, where it expands into a little platform, stayed by braces to the nearest objects that afford a firm hold. In particular situations, where the entrance is exposed to the wind, the mygale, on the approach of the monsoon, extends the strong tissue above it so as to serve as an awning to prevent the access of rain.

The construction of this silken dwelling is exclusively designed for the domestic luxury of the spider; it serves no purpose in trapping or securing prey, and no external disturbance of the web tempts the creature to sally out to surprise an intruder, as the epeira and its congeners would.

By day it remains concealed in its den, whence it issues at night to feed on larvæ and worms, devouring cockroaches and their pupæ, and attacking the millepeds, gryllotalpæ, and other fleshy insects.

Mr. EDGAR L. LAYARD has described 3 an encounter between a Mygale and a cockroach, which he witnessed in the madua of a temple at Alittane, between Anarajapoora and Dambool. When about a yard apart, each [pg 467] discerned the other and stood still, the spider with his legs slightly bent and his body raised, the cockroach confronting him and directing his antennæ with a restless undulation towards his enemy. The spider, by stealthy movements, approached to within a few inches and paused, both parties eyeing each other intently; then suddenly a rush, a scuffle, and both fell to the ground, when the blatta's wings closed, the spider seized it under the throat with his claws, and dragged it into a corner, when the action of his jaws was distinctly audible. Next morning Mr. Layard found that the soft parts of the body had been eaten, nothing but the head, thorax, and clytra remaining.

But, in addition to minor and ignoble prey, the Mygale rests under the imputation of seizing small birds and feasting on their blood. The author who first gave popular currency to this story was Madame MERIAN, a zoological artist of the last century, many of whose drawings are still preserved in the Museums of St. Petersburg, Holland, and England. In a work on the Insects of Surinam, published in 1705 4 , she figured the Mygale aricularia, in the act of devouring a humming-bird. The accuracy of her statement has since been impugned 5 by a correspondent of the Zoological Society of London, on the ground that the mygale makes no net, but lives in recesses, to which no humming-bird would resort; and hence, the writer somewhat illogically declares, that he "disbelieves the existence of any bird-catching spider."

[pg 468]Some years later, however, the same writer felt it incumbent on him to qualify this hasty conclusion 6 , in consequence of having seen at Sydney an enormous spider, the Epeira diadema, in the act of sucking the juices of a bird (the Zosterops dorsalis of Vigors and Horsfield), which, it had caught in the meshes of its geometrical net. This circumstance, however, did not in his opinion affect the case of the Mygale; and even as regards the Epeira, Mr. MacLeay, who witnessed the occurrence, was inclined to believe the instance to be accidental and exceptional; "an exception indeed so rare, that no other person had ever witnessed the fact."

Subsequent observation has, however, served to sustain the story of Madame Merian. 7 Baron Walckenær and Latreille both corroborated it by other authorities; and M. Moreau da Jonnès, who studied the habits of the Mygale in Martinique, says it hunts far and wide in search of its prey, conceals itself beneath leaves for the purpose of surprising them, and climbs the branches of trees to devour the young of the humming-bird, and of the Certhia flaveola. As to its mode of attack, M. Jonnès says that when it throws itself on its victim it clings to it by the double hooks of its tarsi, and strives to reach the back of the head, to insert its jaws between the skull and the vertebræ. 8

[pg 469]For my own part, no instance came to my knowledge in Ceylon of a mygale attacking a bird; but PERCIVAL, who wrote his account of the island in 1805, describes an enormous spider (possibly an Epeirid) thinly covered with hair which "makes webs strong enough to entangle and hold even small birds that form its usual food." 9

The fact of its living on millepeds, blattæ, and crickets, is universally known; and a lady who lived at Marandahn, near Colombo, told me that she had, on one occasion, seen a little house-lizard (gecko) seized and devoured by one of these ugly spiders.

Walckenær has described a spider of large size, under the name of Olios Taprobanius, which is very common in Ceylon, and conspicuous from the fiery hue of the under surface, the remainder being covered with gray hair so short and fine that the body seems almost denuded. It spins a moderate-sized web, hung vertically between two sets of strong lines, stretched one above the other athwart the pathways. Some of the threads thus carried horizontally from tree to tree at a considerable height from the ground are so strong as to cause a painful check across the face when moving quickly against them; and more than once in riding I have had my hat lifted off my head by one of these cords. 10

[pg 470]An officer in the East India Company's Service 11 , in a communication to the Asiatic Society of Bengal, describes the gigantic web of a black and red spider six inches in diameter, (his description of which, both in colour and size, seems to point to some species closely allied to the Olios Taprobanius,) which he saw near Monghyr on the Ganges; in this web "a bird was entangled, and the young spiders, eight in number, and entirely of a brick red colour, were feeding on the carcase." 12

The voracious Galeodes has not yet been noticed in Ceylon; but its carnivorous propensities are well known in those parts of Hindustan, where it is found, and where it lives upon crickets, coleoptera and other insects, as well as small lizards and birds. This "tiger of the insect world," as it has aptly been designated by a gentleman who was a witness to its ferocity 13 , was seen to attack a young sparrow half grown, and seize it by the thigh, which it sawed through. The "savage then caught the bird by the throat, and put an end to its sufferings by cutting off its head." "On another occasion," says the same authority, "Dr. Baddeley confined one of these spiders under a glass wall-shade with two young musk-rats (Sorex Indicus), both of which it destroyed." It must be added, however, that neither in the instance of the bird, of the lizard, or the rats, did the galeodes devour its prey after killing it.

[pg 471]In the hills around Pusilawa, I have seen the haunts of a curious species of long-legged spiders 14 , popularly called "harvest-men," which congregate in hollow trees and in holes in the banks by the roadside, in groups of from fifty to a hundred, that to a casual observer look like bunches of horse-hair. This appearance is produced by the long and slender legs of these creatures, which are of a shining black, whilst their bodies, so small as to be mere specks, are concealed beneath them. The same spider is found in the low country near Galle, but there it shows no tendency to become gregarious. Can it be that they thus assemble in groups in the hills for the sake of accumulated warmth at the cool altitude of 4000 feet?

Ticks.—Ticks are to be classed among the intolerable nuisances to the Ceylon traveller. They live in immense numbers in the jungle 15 , and attaching themselves to the [pg 472] plants by the two forelegs, lie in wait to catch at unwary animals as they pass. A shower of these diminutive vermin will sometimes drop from a branch, if unluckily shaken, and disperse themselves over the body, each fastening on the neck, the ears, and eyelids, and inserting a barbed proboscis. They burrow, with their heads pressed as far as practicable under the skin, causing a sensation of smarting, as if particles of red hot sand had been scattered over the flesh. If torn from their hold, the suckers remain behind and form an ulcer. The only safe expedient is to tolerate the agony of their penetration till a drop of coco-nut oil or the juice of a lime can be applied, when these little furies drop off without further ill consequences. One very large species, dappled with grey, attaches itself to the buffaloes.

Mites.—The Trombidium tinctorum of Hermann is found about Aripo, and generally over the northern provinces,—where after a shower of rain or heavy night's dew, they appear in countless myriads. It is about half an inch long, like a tuft of crimson velvet, and imparts its colouring matter readily to any fluid in which it may be immersed. It feeds on vegetable juices, and is perfectly innocuous. Its European representative, similarly tinted, and found in garden mould, is commonly called the "Little red pillion."

MYRIAPODS.—The certainty with which an accidental pressure or unguarded touch is resented and retorted by a bite, makes the centipede, when it has taken up its temporary abode, within a sleeve or the fold of a dress, by far the most unwelcome of all the Singhalese assailants. The great size, too (little short of a foot in length), [pg 473] to which it sometimes attains, renders it formidable, and, apart from the apprehension of unpleasant consequences from a wound, one shudders at the bare idea of such a hideous creature crawling over the skin, beneath the innermost folds of one's garments.

At the head of the Myriapods, and pre-eminent from a superiorly-developed organisation, stands the genus Cermatia: singular-looking objects; mounted upon slender legs, of gradually increasing length from front to rear, the hind ones in some species being amazingly prolonged, and all handsomely marked with brown annuli in concentric arches. These myriapods are harmless, excepting to woodlice, spiders, and young cockroaches, which form their ordinary prey. They are rarely to be seen; but occasionally at daybreak, after a more than usually abundant repast, they may be observed motionless, and resting with their regularly extended limbs nearly flat against the walls. On being disturbed they dart away with a surprising velocity, to conceal themselves in chinks until the return of night.

But the species to be really dreaded are the true Scolopendræ, which are active and carnivorous, living in holes in old walls and other gloomy dens. One [pg 474] species 16 attains to nearly the length of a foot, with corresponding breadth; it is of a dark purple colour, approaching black, with yellowish legs and antennæ, and in its whole aspect repulsive and frightful. It is strong and active, and evinces an eager disposition to fight when molested. The Scolopendræ are gifted by nature with a rigid coriaceous armour, which does not yield to common pressure, or even to a moderate blow; so that they often escape the most well-deserved and well-directed attempts to destroy them, seeking refuge in retreats which effectually conceal them from sight.

There is a smaller species 17 , that frequents dwelling-houses; it is about one quarter the size of the preceding, and of a dirty olive colour, with pale ferruginous legs. It is this species that generally inflicts the wound, when persons complain of being bitten by a scorpion; and it has a mischievous propensity for insinuating itself into the folds of dress. The bite at first does not occasion more suffering than would arise from the penetration of two coarsely-pointed needles; but after a little time the wound swells, becomes acutely painful, and if it be over a bone or any other resisting part, the sensation is so intolerable as to produce fever. The agony subsides after a few hours' duration. In some cases the bite is unattended by any particular degree of annoyance, and in these instances it is to be supposed that the contents of the poison gland had become exhausted by previous efforts, since, if much tasked, the organ requires rest to enable it to resume its accustomed functions and to secrete a supply of venom.

The Fish-insect.—The chief inconvenience of a [pg 475] residence in Ceylon, both on the coast and in the mountains, is the prevalence of damp, and the difficulty of protecting articles liable to injury from this cause. Books, papers, and manuscripts rapidly decay; especially during the south-west monsoon, when the atmosphere is saturated with moisture. Unless great precautions are taken, the binding fades and yields, the leaves grow mouldy and stained, and letter-paper, in an incredibly short time, becomes so spotted and spongy as to be unfit for use. After a very few seasons of neglect, a book falls to pieces, and its decomposition attracts hordes of minute insects, that swarm to assist in the work of destruction. The concealment of these tiny creatures during daylight renders it difficult to watch their proceedings, or to discriminate the precise species most actively engaged; but there is every reason to believe that the larvæ of the death-watch and numerous acari are amongst the most active. As nature seldom peoples a region supplied with abundance of suitable food, without, at the same time, taking measures of precaution against the disproportionate increase of individuals; so have these vegetable depredators been provided with foes who pursue and feed greedily upon them. These are of widely different genera; but instead of their services being gratefully recognised, they are popularly branded as accomplices in the work of destruction. One of these ill-used creatures is a tiny, tail-less scorpion (Chelifer 18 ), and another is the pretty [pg 476] little silvery creature (Lepisma), called by Europeans the "fish-insect." 19

The latter, which is a familiar genus, comprises several species, of which only two have as yet been described; one is of a large size, most graceful in its movements, and singularly beautiful in appearance, owing to the whiteness of the pearly scales from which its name is derived. These, contrasted with the dark hue of the other parts, and its tri-partite tail, attract the eye as the insect darts rapidly along. Like the chelifer, it shuns the light, hiding in chinks till sunset, but is actively engaged throughout the night feasting on the acari and soft-bodied insects which assail books and papers.

Millepeds.—In the hot dry season, and more especially in the northern portions of the island, the eye is attracted along the edges of the sandy roads by fragments of the dislocated rings of a huge species of millepede 20 , lying in short curved tubes, the cavity admitting the tip of the little finger. When perfect the creature is two-thirds of a foot long, of a brilliant jet black, and with above a hundred yellow legs, which, when moving onward, present the appearance of a series of undulations from rear to front, bearing the [pg 477] animal gently forwards. This Julus is harmless, and may be handled with perfect impunity. Its food consists chiefly of fruits and the roots and stems of succulent vegetables, its jaws not being framed for any more formidable purpose. Another and a very pretty species 21 , quite as black, but with a bright crimson band down the back, and the legs similarly tinted, is common in the gardens about Colombo and throughout the western province.

CRUSTACEA.—The seas around Ceylon abound with marine articulata; but a knowledge of the crustacea of the island is at present a desideratum; and with the exception of the few commoner species that frequent the shores, or are offered in the markets, we are literally without information, excepting the little that can be gleaned from already published systematic works.

In the bazaars several species of edible crabs are exposed for sale; and amongst the delicacies at the tables of Europeans, curries made from prawns and lobsters are the triumphs of the Ceylon cuisine. Of these latter the fishermen sometimes exhibit specimens 22 of extraordinary dimensions and of a beautiful purple hue, variegated with white. Along the level shore north and south of Colombo, and in no less profusion elsewhere, the nimble little Calling Crabs 23 scamper over the moist sands, carrying aloft the enormous hand (sometimes larger than the [pg 478] rest of the body), which is their peculiar characteristic, and which, from its beckoning gesture has suggested their popular name. They hurry to conceal themselves in the deep retreats which they hollow out in the banks that border the sea.

Sand Crabs.—In the same localities, or a little farther inland, the Ocypode 24 burrows in the dry soil, making deep excavations, bringing up literally armfulls of sand; which with a spring in the air, and employing its other limbs, it jerks far from its burrows, distributing it in a circle to the distance of several feet. 25 So inconvenient are the operations of these industrious pests that men are kept regularly employed at Colombo in filling up the holes formed by them on the surface of the Galle face. This, the only equestrian promenade of the capital, is so infested by these active little creatures that accidents often occur through horses stumbling in their troublesome excavations.

Painted Crabs.—On the reef of rocks which lies to the south of the harbour at Colombo, the beautiful little painted crabs 26 , distinguished by dark red markings on a yellow ground, may be seen all day long running nimbly in the spray, and ascending and descending in security the almost perpendicular sides of the rocks which are washed by the waves. Paddling Crabs 27 , with the hind pair of legs terminated by flattened plates to assist them in swimming, are brought up in the fishermen's nets. Hermit Crabs take possession of the deserted shells of the univalves, and crawl in pursuit of garbage along the moist beach. Prawns and shrimps furnish delicacies [pg 479] for the breakfast table; and the delicate little pea crab, Pontonia inflata 28 , recalls its Mediterranean congener 29 , which attracted the attention of Aristotle, from taking up its habitation in the shell of the living pinna.

ANNELIDÆ.—The marine Annelides of the island have not as yet been investigated; a cursory glance, however, amongst the stones, on the beach at Trincomalie and in the pools that afford convenient basins for examining them, would lead to the belief that the marine species are not numerous; tubicole genera, as well as some nereids, are found, but there seems to be little diversity, though it is not impossible that a closer scrutiny might be repaid by the discovery of some interesting forms.

Leeches.—Of all the plagues which beset the traveller in the rising grounds of Ceylon, the most detested are the land leeches. 30 They are not frequent in the plains, [pg 480] which are too hot and dry for them; but amongst the rank vegetation in the lower ranges of the hill country, [pg 481] which is kept damp by frequent showers, they are found in tormenting profusion. They are terrestrial, never visiting ponds or streams. In size they are about an inch in length, and as fine as a common knitting needle; but they are capable of distension till they equal a quill in thickness, and attain a length of nearly two inches. Their structure is so flexible that they can insinuate themselves through the meshes of the finest stocking, not only seizing on the feet and ankles, but ascending to the back and throat and fastening on the tenderest parts of the body. In order to exclude them, the coffee planters, who live amongst these pests, are obliged to envelope their legs in "leech gaiters" made of closely woven cloth. The natives smear their bodies with oil, tobacco ashes, or lemon juice 31 ; the latter serving not only to stop the flow of blood, but to expedite the healing of the wounds. In moving, the land leeches have the power of planting one extremity on the earth and raising the other perpendicularly to watch for their victim. Such is their vigilance and instinct, that on [pg 482] the approach of a passer-by to a spot which they infest, they may be seen amongst the grass and fallen leaves on the edge of a native path, poised erect, and preparing for their attack on man and horse. On descrying their prey they advance rapidly by semi-circular strides, fixing one end firmly and arching the other forwards, till by successive advances they can lay hold of the traveller's foot, when they disengage themselves from the ground and ascend his dress in search of an aperture to enter. In these encounters the individuals in the rear of a party of travellers in the jungle invariably fare worst, as the leeches, once warned of their approach, congregate with singular celerity. Their size is so insignificant, and the wound they make is so skilfully punctured, that both are generally imperceptible, and the first intimation of their onslaught is the trickling of the blood or a chill feeling of the leech when it begins to hang heavily on the skin from being distended by its repast. Horses are driven wild by them, and stamp the ground in fury to shake them from their fetlocks, to which they hang in bloody tassels. The bare legs of the palankin bearers and coolies are a favourite resort; and, as their hands are too much engaged to be spared to pull them off, the leeches hang like bunches of grapes round their ankles; and I have seen the blood literally flowing over the ledge of a European's shoe from their innumerable bites. In healthy constitutions the wounds, if not irritated, generally heal, occasioning no other inconvenience than a slight inflammation and itching; but in those with a bad state of body, the punctures, if rubbed, are liable to degenerate into ulcers, which may lead to the loss of limb or even of life. Both Marshall and Davy mention, that during [pg 483] the march of troops in the mountains, when the Kandyans were in rebellion, in 1818, the soldiers, and especially the Madras sepoys, with the pioneers and coolies, suffered so severely from this cause that numbers perished. 32

One circumstance regarding these land leeches is remarkable and unexplained; they are helpless without moisture, and in the hills where they abound at all other times, they entirely disappear during long droughts;—yet re-appear instantaneously on the very first fall of rain; and in spots previously parched, where not one was visible an hour before, a single shower is sufficient to reproduce them in thousands, lurking beneath the decaying leaves, or striding with rapid movements across the gravel. Whence do they re-appear? Do they, too, take a "summer sleep," like the reptiles, molluscs, and tank fishes? or may they, like the Rotifera, be dried up and preserved for an indefinite period, resuming their vital activity on the mere recurrence of moisture? 33

Besides a species of the medicinal leech, which 34 is [pg 484] found in Ceylon, nearly double the size of the European one, and with a prodigious faculty of engorging blood, there is another pest in the low country, which is a source of considerable annoyance, and often of loss, to the husbandman. This is the cattle leech 35 , which infests the stagnant pools, chiefly in the alluvial lands around the base of the mountain zone, whither the cattle resort by day, and the wild animals by night, to quench their thirst and to bathe. Lurking amongst the rank vegetation that fringes these deep pools, and hid by the broad leaves, or concealed among the stems and roots covered by the water, there are quantities of these pests in wait to attack the animals on their approach to drink. Their natural food consists of the juices of lumbrici and other invertebrata; but they [pg 485] generally avail themselves of the opportunity afforded by the dipping of the muzzles of the animals in the water to fasten on their nostrils, and by degrees to make their way to the deeper recesses of the nasal passages, and the mucous membranes of the throat and gullet. As many as a dozen have been found attached to the epiglottis and pharynx of a bullock, producing such irritation and submucous effusion that death has eventually ensued; and so tenacious are the leeches that even after death they retain their hold for some hours. 36

The Rotifer, a singular creature, although it can only truly live in water, inhabits the moss on house-tops, dying each time the sun dries up its place of retreat, to revive as often as a shower of rain supplies it with the moisture essential to its existence; thus employing several years to exhaust the eighteen days of life which nature has allotted to it. These creatures were discovered by LEUWENHOECK, and have become the types of a class already numerous, which undergo the same conditions of life, and possess the same faculty. Besides the Rotifera, the Tardigrades, (which belong to the Acari,) and certain paste-eels, all exhibit a similar phenomenon. [pg 487] But although these different species may die and be resuscitated several times in succession, this power has its limits, and each successive experiment generally proves fatal to one or more individuals. SPALLANZANI, in his experiments on the Rotifera, did not find that any survived after the sixteenth alternation of desiccation and damping, but paste-eels bore seventeen of those vicissitudes.

SPALLANZANI, after thoroughly drying sand rich in Rotifera, kept it for more than three years, moistening portions taken from it every five or six months. BAKER went further still in his experiments on paste-eels, for he kept the paste from which they had been taken, without moistening it in any way, for twenty-seven years, and at the end of that time the eels revived on being immersed in a drop of water. If they had exhausted their lives all at once and without these intermissions, these Rotifera and paste-eels would not have lived beyond sixteen or eighteen consecutive days.

To remove all doubt as to the complete desiccation of the animalcules experimented on by SPALLANZANI and BAKER, M. DOYÈRE has published, in the Annales des Sciences Naturales for 1842, the results of his own observation, in cases in which the mosses containing the insects were dried under the receiver of an air-pump and left there for a week; after which they were placed in a stove heated to 267° Fahr., and yet, when again immersed in water, a number of the Rotifera became as lively as ever.

Further particulars of these experiments will be found in the Appendix to the Rambles of a Naturalist, &c., by M. QUARTREFAGE.

1Species of the true Tarentula are not uncommon in Ceylon; they are all of very small size, and perfectly harmless.

2See Plate opposite.

3Ann. and Mag. Nat. Hist. May, 1853.

4Dissertatio de Generatione et Metamorphosibus Insectorum Surinamensium, Amst. 1701. Fol.

5By Mr. MACLEAY in a paper communicated to the Zoological Society of London, Proc. 1834, p. 12.

6See Ann. and Mag. of Nat. Hist. for 1842, vol. viii. p. 324.

7See authorities quoted by Mr. SHUCKARD in the Ann. and Mag. of Nat. Hist. 1842, vol. viii. p. 436, &c.

8At a meeting of the Entomological Society, July 20, 1855, a paper was read by Mr. H.W. BATES, who stated that in 1849 at Cameta in Brazil, he "was attracted by a curious movement of the large grayish brown Mygale on the trunk of a vast tree: it was close beneath a deep crevice or chink in the tree, across which this species weaves a dense web, at one end open for its exit and entrance. In the present instance the lower part of the web was broken, and two small finches were entangled in its folds. The finch was about the size of the common Siskin of Europe, and he judged the two to be male and female; one of them was quite dead, but secured in the broken web; the other was under the body of the spider, not quite dead, and was covered in parts with a filthy liquor or saliva exuded by the monster. "The species of spider," Mr. Bates says, "I cannot name; it is wholly of a gray brown colour, and clothed with coarse pile." "If the Mygales," he adds, "did not prey upon vertebrated animals, I do not see how they could find sufficient subsistence."—The Zoologist, vol. xiii. p. 480.

9PERCIVAL'S Ceylon, p. 313.

10Over the country generally are scattered species of Gasteracantha, remarkable for their firm shell-covered bodies, with projecting knobs arranged in pairs. In habit these anomalous-looking Epeirdæ appear to differ in no respect from the rest of the family, waylaying their prey in similar situations and in the same manner.

Another very singular subgenus, met with in Ceylon, is distinguished by the abdomen being dilated behind, and armed with two long spines, arching obliquely backwards. These abnormal kinds are not so handsomely coloured as the smaller species of typical form.

11Capt. Sherwill.

12Jour. Asiat. Soc. Bengal, 1850, vol. xix. p. 475.

13Capt. Hutton. See a paper on the Galeodes voræ in the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, vol. xi. Part 11. p. 860.

14Phalangium bisignatum.

15Dr. HOOKER, in his Himalayan Journal, vol. i. p. 279, in speaking of the multitude of those creatures in the mountains of Nepal, wonders what they tend to feed on, as in these humid forests in which they literally swarmed, there was neither pathway nor animal life. In Ceylon they abound everywhere in the plains on the low brush-wood; and in the very driest seasons they are quite as numerous as at other times. In the mountain zone, which is more humid, they are less prevalent. Dogs are tormented by them: and they display something closely allied to cunning in always fastening on an animal in those parts where they cannot be torn off by his paws; on his eye-brows, the tips of his ears, and the back of his neck. With a corresponding instinct I have always observed in the gambols of the Pariah dogs, that they invariably commence their attentions by mutually gnawing each other's ears and necks, as if in pursuit of ticks from places from which each is unable to expel them for himself. Horses have a similar instinct; and when they meet, they apply their teeth to the roots of the ears of their companions, to the neck and the crown of the head. The buffaloes and oxen are relieved of ticks by the crows which rest on their backs as they browse, and free them from these pests. In the low country the same acceptable office is performed by the "cattle-keeper heron" (Ardea bubulcus), which is "sure to be found in attendance on them while grazing; and the animals seem to know their benefactors, and stand quietly, while the birds peck their tormentors from their flanks."—Mag. Nat. Hist. p. 111, 1844.

16Scolopendra crassa, Temp.

17Scolopendra pallipes.

18Of the first of these, three species have been noticed in Ceylon, all with the common characteristics of being nocturnal, very active, very minute, of a pale chesnut colour, and each armed with a crab-like claw. They are

Chelifer Librorum, Temp.

Chelifer oblongus, Temp.

Chelifer acaroides, Hermann.

Dr. Templeton appears to have been puzzled to account for the appearance of the latter species in Ceylon, so far from its native country, but it has most certainly been introduced from Europe, in Dutch or Portuguese books.

19Lepisma niveo-fasciata, Templeton, and L. niger, Temp. It was called "Lepisma" by Fabricius, from its fish-like scales. It has six legs, filiform antenna, and the abdomen terminated by three elongated setæ, two of which are placed nearly at right angles to the central one. LINNÆUS states that the European species, with which book collectors are familiar, was first brought in sugar ships from America. Hence, possibly, these are more common in seaport towns in the South of England and elsewhere, and it is almost certain that, like the chelifer, one of the species found on book-shelves in Ceylon, has been brought thither from Europe.

20Julus ater.

21Julus carnifex, Fab.

22Palinurus ornatus, Fab. P—n. s.

23Gelasimus tetragonon? Edw.; G. annulipes? Edw.; G. Dussumieri? Edw.

24Ocypode ceratophthamus. Pall.

25Ann. Nat. Hist. April, 1852. Paper by Mr. EDGAR L. LAYARD.

26Grapsus strigosus, Herbst.

27Neptunus pelagicus, Linn.; N. sanguinolentus, Herbst, &c. &c.

28MILNE EDW., Hist. Nat. Crust., vol. ii. p. 360.

29Pinnotheres veterum.

30Hæmadipsa Ceylanica. Bose. Blainv. These pests are not, however, confined to Ceylon, they infest the lower ranges of the Himalaya.—HOOKER, vol. i. p. 107; vol. ii. p. 54. THUNBERG, who records (Travels, vol. iv. p. 232) having seen them in Ceylon, likewise met with them in the forests and slopes of Batavia. MARSDEN (Hist. p. 311) complains of them dropping on travellers in Sumatra. KNORR found them at Japan; and it is affirmed that they abound in islands farther to the eastward. M. GAY encountered them in Chili.—(MOQUIN-TANDON, Hirudinées, p. 211, 346). It is very doubtful, however, whether all these are to be referred to one species. M. DE BLAINVILLE, under H. Ceylanica, in the Dict. de Scien. Nat. vol. xlvii. p. 271, quotes M. Bosc as authority for the kind, which that naturalist describes being "rouges et tachetées;" which is scarcely applicable to the Singhalese species. It is more than probable therefore, considering the period at which M. BOSC wrote, that he obtained his information from travellers to the further east, and has connected with the habitat universally ascribed to them from old KNOX'S work (Part 1. chap. vi.) a meagre description, more properly belonging to the land leech of Batavia or Japan. In all likelihood, therefore, there may be a H. Boscii, distinct from the H. Ceylanica. That which is found in Ceylon is round, a little flattened on the inferior surface, largest at the anal extremity, thence gradually tapering forward, and with the anal sucker composed of four rings, and wider in proportion than in other species.

It is of a clear brown colour, with a yellow stripe the entire length of each side, and a greenish dorsal one. The body is formed of 100 rings; the eyes, of which there are five pairs, are placed in an arch on the dorsal surface; the first four pairs occupying contiguous rings (thus differing from the water-leeches, which have an unoccupied ring betwixt the third and fourth); the fifth pair are located on the seventh ring, two vacant rings intervening. To Mr. Thwaites, Director of the Botanic Garden at Peradenia, who at my request examined their structure minutely, I am indebted for the following most interesting particulars respecting them. "I have been giving a little time to the examination of the land leech. I find it to have five pairs of ocelli, the first four seated on corresponding segments, and the posterior pair on the seventh segment or ring, the fifth and sixth rings being eyeless (fig. A). The mouth is very retractile, and the aperture is shaped as in ordinary leeches. The serratures of the teeth, or rather the teeth themselves, are very beautiful. Each of the three 'teeth,' or cutting instruments, is principally muscular, the muscular body being very clearly seen. The rounded edge in which the teeth are set appears to be cartilaginous in structure; the teeth are very numerous, (fig. B); but some near the base have a curious appendage, apparently (I have not yet made this out quite satisfactorily) set upon one side. I have not yet been able to detect the anal or sexual pores. The anal sucker seems to be formed of four rings, and on each side above is a sort of crenated flesh-like appendage. The tint of the common species is yellowish-brown or snuff-coloured, streaked with black, with a yellow-greenish dorsal, and another lateral line along its whole length. There is a larger species to be found in this garden with a broad green dorsal fascia; but I have not been able to procure one although I have offered a small reward to any coolie who will bring me one." In a subsequent communication Mr. Thwaites remarks "that the dorsal longitudinal fascia is of the same width as the lateral ones, and differs only in being perhaps slightly more green; the colour of the three fasciæ varies from brownish-yellow to bright green." He likewise states "that the rings which compose the body are just 100, and the teeth 70 to 80 in each set, in a single row, except to one end, where they are in a double row."

31The Minorite friar, ODORIC of Portenau. writing in A.D. 1320, says that the gem-finders who sought the jewels around Adam's Peak, "take lemons which they peel, anointing themselves with the juice thereof, so that the leeches may not be able to hurt them."—HAKLUYT, Voy. vol. ii. p. 58.

32DAVY'S Ceylon, p. 104; MARSHALL'S Ceylon, p. 15.

33See an account of the Rotifera and their faculty of repeated vivifaction, in the note appended to this chapter.

34Hirudo sanguisorba. The paddi-field leech of Ceylon, used for surgical purposes, has the dorsal surface of blackish olive, with several longitudinal striæ, more or less defined; the crenated margin yellow. The ventral surface is fulvous, bordered laterally with olive; the extreme margin yellow. The eyes are ranged as in the common medicinal leech of Europe; the four anterior ones rather larger than the others. The teeth are 140 in each series, appearing as a single row; in size diminishing gradually from one end, very close set, and about half the width of a tooth apart. When full grown, these leeches are about two inches long, but reaching to six inches when extended. Mr. Thwaites, to whom I am indebted for these particulars, adds that he saw in a tank at Kolona Korle leeches which appeared to him flatter and of a darker colour than those described above, but that he had not an opportunity of examining them particularly.

Mr. Thwaites states that there is a smaller tank leech of an olive-green colour, with some indistinct longitudinal striæ on the upper surface; the crenated margin of a pale yellowish-green; ocelli as in the paddi-field leech; length, one inch at rest, three inches when extended.

Mr. E.L. LAYARD informs us, Mag. Nat. Hist. p. 225, 1853, that a bubbling spring at the village of Tonniotoo, three miles S.W. of Moeletivoe, supplies most of the leeches used in the island. Those in use at Colombo are obtained in the immediate vicinity.

35Hæmopsis paludum. In size the cattle leech of Ceylon is somewhat larger than the medicinal leech of Europe: in colour it is of a uniform brown without bands, unless a rufous margin may be so considered. It has dark striæ. The body is somewhat rounded, flat when swimming, and composed of rather more than ninety rings. The greatest dimension is a little in advance of the anal sucker; the body thence tapers to the other extremity, which ends in an upper lip projecting considerably beyond the mouth. The eyes, ten in number, are disposed as in the common leech. The mouth is oval, the biting apparatus with difficulty seen, and the teeth not very numerous. The bite is so little acute that the moment of attachment, and the incision of the membrane is scarcely perceived by the sufferer from its attack.

36[pg 488]Even men, when stooping to drink at a pool, are not safe from the assault of the cattle leeches. They cannot penetrate the human skin, but the delicate membrane of the mucous passages is easily ruptured by their serrated jaws. Instances have come to my knowledge of Europeans into whose nostrils they had gained admission and caused serious disturbance.