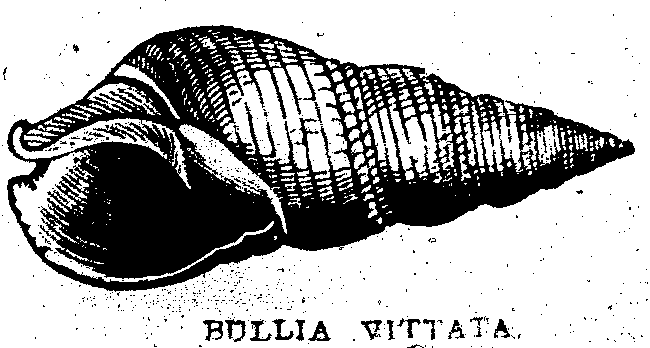

BULLIA VITTATA

BULLIA VITTATACeylon has long been renowned for the beauty and variety of the shells which abound in its seas and inland waters, and in which an active trade has been organised by the industrious Moors, who clean them with great expertness, arrange them in satin-wood boxes, and send them to Colombo and all parts of the island for sale. In general, however, these specimens are more prized for their beauty than valued for their rarity, though some of the "Argus" cowries 1 have been sold as high as four guineas a pair.

One of the principal sources whence their supplies are derived is the beautiful Bay of Venloos, to the north of Batticaloa, formed by the embouchure of the Natoor river. The scenery at this spot is enchanting. The sea is overhung by gentle acclivities wooded to the summit; and in an opening between two of these eminences the river flows through a cluster of little islands covered with mangroves and acacias. A bar of rocks projects across it, at a short distance from the shore; and these are frequented all day long by pelicans, that come at [pg 370] sunrise to fish, and at evening return to their solitary breeding-places remote from the beach. The strand is literally covered with beautiful shells in rich profusion, and the dealers from Trincomalie know the proper season to visit the bay for each particular description. The entire coast, however, as far north as the Elephant Pass, is indented by little rocky inlets, where shells of endless variety may be collected in great abundance. 2 During the north-east monsoon a formidable surf bursts upon the shore, which is here piled high with mounds of yellow sand; and the remains of shells upon the water mark show how rich the sea is in mollusca. Amongst them are prodigious numbers of the ubiquitous violet-coloured Ianthina 3 , which rises when the ocean is calm, and by means of its inflated vesicles floats lightly on the surface.

The trade in shells is one of extreme antiquity in Ceylon. The Gulf of Manaar has been fished from the earliest times for the large chank shell, Turbinella [pg 371] rapa, to be exported to India, where it is still sawn into rings and worn as anklets and bracelets by the women of Hindustan. Another use for these shells is their conversion into wind instruments, which are sounded in the temples on all occasions of ceremony. A chank, in which the whorls, instead of running from left to right, as in the ordinary shell, are reversed, and run from right to left, is regarded with such reverence that a specimen formerly sold for its weight in gold, but one may now be had for four or five pounds. COSMAS INDICO-PLEUSTES, writing in the fifth century, describes a place on the west coast of Ceylon, which he calls Marallo, and says it produced "[Greek: kochlious]," which THEVENOT translates "oysters;" in which case Marallo might be conjectured to be Bentotte, near Colombo, which yields the best edible "oysters" in Ceylon. 4 But the shell in question was most probably the chank, and Marallo was Mantotte, off which it is found in great numbers. 5 In fact, two centuries later Abouzeyd, an Arab, who wrote an account of the trade and productions of India, speaks of these shells by the name they still bear, which he states to be schenek 6 ; but "schenek" is not an Arabic word, and is merely an attempt to spell the local term, chank, in Arabic characters.

[pg 372]BERTOLACCI mentions a curious local peculiarity 7 observed by the fishermen in the natural history of the chank. "All shells," he says, "found to the northward of a line drawn from a point about midway from Manaar to the opposite coast (of India) are of the kind called patty, and are distinguished by a short flat head; and all those found to the southward of that line are of the kind called pajel, and are known from having a longer and more pointed head than the former. Nor is there ever an instance of deviation from this singular law of nature. The Wallampory, or 'right-hand chanks,' are found of both kinds."

This tendency of particular localities to re-produce certain specialities of form and colour is not confined to the sea or to the instance of the chank shell. In the gardens which line the suburbs of Galle in the direction of Matura the stems of the coco-nut and jak trees are profusely covered with the shells of the beautiful striped Helix hamastoma. Stopping frequently to collect them, I was led to observe that each separate garden seemed to possess a variety almost peculiar to itself; in one the mouth of every individual shell was red; in another, separated from the first only by a wall, black; and in others (but less frequently) pure white; whilst the varieties of external colouring were equally local. In one enclosure they were nearly all red, and in an adjoining one brown. 8

[pg 373]A trade more ancient by far than that carried on in chanks, and infinitely more renowned, is the fishery of pearls on the west coast of Ceylon, bordering the Gulf of Manaar. No scene in Ceylon presents so dreary an aspect as the long sweep of desolate shore to which, from time immemorial, adventurers have resorted from the uttermost ends of the earth in search of the precious pearls for which this gulf is renowned. On approaching it from sea the only perceptible landmark is a building erected by Lord Guildford, as a temporary residence for the Governor, and known by the name of the "Doric," from the style of its architecture. A few coco-nut palms appear next above the low sandy beach, and presently are discovered the scattered houses which form the villages of Aripo and Condatchy.

Between these two places, or rather between the Kalaar and Arrive river, the shore is raised to a height of many feet, by enormous mounds of shells, the accumulations of ages, the millions of oysters 9 , robbed of their pearls, having been year after year flung into heaps, that extend for a distance of many miles.

During the progress of a pearl-fishery, this singular and dreary expanse becomes suddenly enlivened by the crowds who congregate from distant parts of India; a town is improvised by the construction of temporary dwellings, huts of timber and cajans 10 , with tents of palm leaves or canvas; and bazaars spring up, to feed the multitude on land, as well as the seamen and divers in the fleets of boats that cover the bay.

[pg 374]I visited the pearl banks officially in 1848 in company with Capt. Stenart, the official inspector. My immediate object was to inquire into the causes of the suspension of the fisheries, and to ascertain the probability of reviving a source of revenue, the gross receipts from which had failed for several years to defray the cost of conservancy. In fact, between 1837 and 1854, the pearl banks were an annual charge, instead of producing an annual income, to the colony. The conjecture, hastily adopted, to account for the disappearance of mature shells, had reference to mechanical causes; the received hypothesis being that the young broods had been swept off their accustomed feeding grounds, by the establishment of unusual currents, occasioned by deepening the narrow passage between Ceylon and India at Paumbam. It was also suggested, that a previous Governor, in his eagerness to replenish the colonial treasury, had so "scraped" and impoverished the beds as to exterminate the oysters. To me, neither of these suppositions appeared worthy of acceptance; for, in the frequent disruptions of Adam's Bridge, there was ample evidence that the currents in the Gulf of Manaar had been changed at former times without destroying the pearl beds: and moreover the oysters had disappeared on many former occasions, without any imputation of improper management on the part of the conservators; and returned after much longer intervals of absence than that which fell under my own notice, and which was then creating serious apprehension in the colony.

A similar interruption had been experienced between 1820 and 1828: the Dutch had had no fishing for [pg 375] twenty-seven years, from 1768 till 1796 11 ; and they had been equally unsuccessful from 1732 till 1746. The Arabs were well acquainted with similar vicissitudes, and Albyronni (a contemporary of Avicenna), who served under Mahmoud of Ghuznee, and wrote in the eleventh century, says that the pearl fishery, which formerly existed in the Gulf of Serendib, had become exhausted in his time, simultaneously with the appearance of a fishery at Sofala, in the country of the Zends, where pearls were unknown before; and hence, he says, arose the conjecture that the pearl oyster of Serendib had migrated to Sofala. 12

It appeared to me that the explanation of the phenomenon was to be sought, not merely in external causes, but also in the instincts and faculties of the animals themselves, and, on my return to Colombo, I ventured to renew a recommendation, which had been made years before, that a scientific inspector should be appointed to study the habits and the natural history of the pearl-oyster, and that his investigations should be facilitated by the means at the disposal of the Government.

Dr. Kelaart was appointed to this office, by Sir H.G. Ward, in 1857, and his researches speedily developed results of great interest. In opposition to the received opinion that the pearl-oyster is incapable of voluntary [pg 376] movement, and unable of itself to quit the place to which it is originally attached 13 , he demonstrated, not only that it possesses locomotive powers, but also that their exercise is indispensable to its oeconomy when obliged to search for food, or compelled to escape from local impurities. He showed that, for this purpose, it can sever its byssus, and re-form it at pleasure, so as to migrate and moor itself in favourable situations. 14 The establishment of this important fact may tend to solve the mystery of the occasional disappearances of the oyster; and if coupled with the further discovery that it is susceptible of translation from place to place, and even from salt to brackish water, it seems reasonable to expect that beds may be formed with advantage in positions suitable for its growth and protection. Thus, like the edible oyster of our own shores, the pearl-oyster may be brought within the domain of pisciculture, and banks may be created in suitable places, just as the southern shores of France are now being colonised with oysters, under the direction of M. Coste. 15 The operation of sowing the sea with pearl, should the experiment succeed, would be as gorgeous in reality, as it is grand in conception: and the wealth of Ceylon, in her "treasures of the deep," might eclipse the renown of her gems when she merited the title of the "Island of Rubies."

On my arrival at Aripo, the pearl-divers, under the orders of their Adapanaar, put to sea, and commenced [pg 377] the examination of the banks. 16 The persons engaged in this calling are chiefly Tamils and Moors, who are trained for the service by diving for chanks. The pieces of apparatus employed to assist the diver in his operations are exceedingly simple in their character: they consist merely of a stone, about thirty pounds' weight, (to accelerate the rapidity of his descent,) which is suspended over the side of the boat, with a loop attached to it for receiving the foot; and of a net-work basket, which he takes down to the bottom and fills with the oysters as he collects them. MASSOUDI, one of the earliest Arabian geographers, describing, in the ninth century, the habits of the pearl-divers in the Persian Gulf, says that, before descending, each filled his ears with cotton steeped in oil, and compressed his nostrils by a piece of tortoise-shell. 17 This practice continues there to the present day 18 ; but the diver of Ceylon rejects all such expedients; he inserts his foot in the "sinking stone" and inhales a full breath; presses his nostrils with his left hand; raises his body as high [pg 378] as possible above water, to give force to his descent: and, liberating the stone from its fastenings, he sinks rapidly below the surface. As soon as he has reached the bottom, the stone is drawn up, and the diver, throwing himself on his face, commences with alacrity to fill his basket with oysters. This, on a concerted signal, is hauled rapidly to the surface; the diver assisting his own ascent by springing on the rope as it rises.

Improbable tales have been told of the capacity which these men acquire of remaining for prolonged periods under water. The divers who attended on this occasion were amongst the most expert on the coast, yet not one of them was able to complete a full minute below. Captain Steuart, who filled for many years the office of Inspector of the Pearl Banks, assured me that he had never known a diver to continue at the bottom longer than eighty-seven seconds, nor to attain a greater depth than thirteen fathoms; and on ordinary occasions they seldom exceeded fifty-five seconds in nine fathom water 19 .

[pg 379]The only precaution to which the Ceylon diver devotedly resorts, is the mystic ceremony of the shark-charmer, whose exorcism is an indispensable preliminary to every fishery. His power is believed to be hereditary; nor is it supposed that the value of his incantations is at all dependent upon the religious faith professed by the operator, for the present head of the family happens to be a Roman Catholic. At the time of our visit this mysterious functionary was ill and unable to attend; but he sent an accredited substitute, who assured me that although he himself was ignorant of the grand and mystic secret, the mere fact of his presence, as a representative of the higher authority, would be recognised and respected by the sharks.

Strange to say, though the Gulf of Manaar abounds with these hideous creatures, not more than one well authenticated accident 20 is known to have occurred from this source during any pearl fishery since the British have had possession of Ceylon. In all probability the reason is that the sharks are alarmed by the unusual number of boats, the multitude of divers, the noise of the crews, the incessant plunging of the sinking stones, and the descent and ascent of the baskets filled with shells. The dark colour of the divers themselves may also be a protection; whiter skins might not experience an equal impunity. Massoudi relates that the divers of the Persian Gulf were so conscious of this advantage of colour, that they were accustomed to blacken their limbs, in order to baffle the sea monsters. 21

The result of our examination of the pearl banks, on this occasion, was such as to discourage the hope of an early fishery. The oysters in point of number were abundant, but in size they were little more than "spat," the largest being barely a fourth of an inch in diameter. As at least seven years are required to furnish the growth at which pearls may be sought with advantage 22 , [pg 380] the inspection served only to suggest the prospect (which has since been realised) that in time the income from this source might be expected to revive;—and, forced to content ourselves with this anticipation, we weighed anchor from Condatchy, on the 30th March, and arrived on the following day at Colombo.

The banks of Aripo are not the only localities, nor is the acicula the only mollusc, by which pearls are furnished. The Bay of Tamblegam, connected with the magnificent harbour of Trincomalie, is the seat of another pearl fishery, and the shell which produces them is the thin transparent oyster (Placuna placenta). whose clear white shells are used, in China and elsewhere, as a substitute for window glass. They are also collected annually for the sake of the diminutive pearls contained in them. These are exported to the coast of India, to be calcined for lime, which the luxurious affect to chew with their betel. These pearls are also burned in the mouths of the dead. So prolific are the mollusca of the Placuna, that the quantity of shells taken by the licensed renter in the three years prior to 1858, could not have been less than eighteen millions. 23 They delight in brackish water, and on more than one recent occasion, an excess of either salt water or fresh has proved fatal to great numbers of them.

[pg 381]1, 2. The young brood or spat.

3. Four months old.

4. Six months old.

5. One year old.

6. Two years old.

On the occasion of a visit which I made to Batticaloa. in September, 1848, I made some inquiries relative to a story which had reached me of musical sounds, said to be often heard issuing from the bottom of the lake, at several places, both above and below the ferry opposite the old Dutch Fort; and which the natives suppose to proceed from some fish peculiar to the locality. The report was confirmed in all its particulars, and one of the spots whence the sounds proceed was pointed out between the pier and a rock that intersects the channel, two or three hundred yards to the eastward. They were said to be heard at night, and most distinctly when the moon was nearest the full, and they were described as resembling the faint sweet notes of an Æolian harp. I sent for some of the fishermen, who said they were perfectly aware of the fact, and that their fathers had always known of the existence of the musical sounds, heard, they said, at the spot alluded to, but only during the dry season, as they cease when the lake is swollen by the freshes after the rain. They believed them to proceed not from a fish, but from a shell, which is known by the Tamil name of (oorie cooleeroo cradoo, or) the "crying shell," a name in which the sound seems to have been adopted as an echo to the sense. I sent them in search of the shell, and they returned bringing me some living specimens of different shells, chiefly littorina and cerithium. 24

[pg 382]In the evening when the moon rose, I took a boat and accompanied the fishermen to the spot. We rowed about two hundred yards north-east of the jetty by the fort gate; there was not a breath of wind, nor a ripple except those caused by the dip of our oars. On coming to the point mentioned, I distinctly heard the sounds in question. They came up from the water like the gentle thrills of a musical chord, or the faint vibrations of a wine-glass when its rim is rubbed by a moistened finger. It was not one sustained note, but a multitude of tiny, sounds, each clear and distinct in itself; the sweetest treble mingling with the lowest bass. On applying the ear to the woodwork of the boat, the vibration was greatly increased in volume. The sounds varied considerably at different points, as we moved across the lake, as if the number of the animals from which they proceeded was greatest in particular spots; and occasionally we rowed out of hearing of them altogether, until on returning to the original locality the sounds were at once renewed.

This fact seems to indicate that the causes of the sounds, whatever they may be, are stationary at several points; and this agrees with the statement of the natives, that they are produced by mollusca, and not by fish. They came evidently and sensibly from the depth of the lake, and there was nothing in the surrounding circumstances to support the conjecture that they could be the reverberation of noises made by insects on the shore conveyed along the surface of the water; for they were loudest and most distinct at points where the nature of the land, and the intervention of the fort and its buildings, forbade the possibility of this kind of conduction.

[pg 383]Sounds somewhat similar are heard under water at some places on the western coast of India, especially in the harbour of Bombay. 25 At Caldera, in Chili, musical cadences are stated to issue from the sea near the landing-place; they are described as rising and falling fully four notes, resembling the tones of harp strings, and mingling like those at Batticaloa, till they produce a musical discord of great delicacy and sweetness. The [pg 384] same interesting phenomenon has been observed at the mouth of the Pascagoula, in the State of Mississippi, and of another river called the "Bayou coq del Inde," on the northern shore of the Gulf of Mexico. The animals from which they proceed have not been identified at either of these places, and the mystery remains unsolved, whether the sounds at Batticaloa are given forth by fishes or by molluscs.

Certain fishes are known to utter sounds when removed from the water 26 , and some are capable of making noises when under it 27 ; but all the circumstances connected with the sounds which I heard at Batticaloa are unfavourable to the conjecture that they were produced by either.

Organs of hearing have been clearly ascertained to [pg 385] exist, mot only in fishes 28 , but in mollusca. In the oyster the presence of an acoustic apparatus of the simplest possible construction has been established by the discoveries of Siebold 29 , and from our knowledge of the reciprocal relations existing between the faculties of hearing and of producing sounds, the ascertained existence of the one affords legitimate grounds for inferring the coexistence of the other in animals of the same class. 30

Besides, it has been clearly established, that one at least of the gasteropoda is furnished with the power of producing sounds. Dr. Grant, in 1826, communicated to the Edinburgh Philosophical Society the fact, that on placing some specimens of the Tritonia arborescens in a glass vessel filled with sea water, his attention was attracted by a noise which he ascertained to proceed from these mollusca. It resembled the "clink" of a steel wire on the side of the jar, one stroke only being given at a time, and repeated at short intervals. 31

The affinity of structure between the Tritonia and the mollusca inhabiting the shells brought to me at Batticaloa, might justify the belief of the natives of Ceylon, that the latter are the authors of the sounds I heard; and the description of those emitted by the former as given by Dr. Grant, so nearly resemble them, that I have always regretted my inability, on the occasion [pg 386] of my visits to Batticaloa, to investigate the subject more narrowly. At subsequent periods I have since renewed my efforts, but without success, to obtain specimens or observations of the habits of the living mollusca.

The only species afterwards sent to me were Cerithia; but no vigilance sufficed to catch the desired sounds, and I still hesitate to accept the dictum of the fishermen, as the same mollusc abounds in all the other brackish estuaries on the coast; and it would be singular, if true, that the phenomenon of its uttering a musical note should be confined to a single spot in the lagoon of Batticaloa. 32

Although naturalists have long been familiar with the marine testacea of Ceylon, no successful attempt has yet been made to form a classified catalogue of the species; and I am indebted to the eminent conchologist, Mr. Sylvanus Hanley, for the list which accompanies this notice.

In drawing it up, Mr. Hanley observes that he found it a task of more difficulty than would at first be surmised, owing to the almost total absence of reliable data from which to construct it. Three sources were available: collections formed by resident naturalists, the contents of the well-known satin-wood boxes prepared at Trincomalie, and the laborious elimination of locality from the habitats ascribed to all the known species in the multitude of works on conchology in general.

But, unfortunately, the first resource proved fallacious. There is no large collection in this country composed exclusively of Ceylon shells;—and as the very few cabinets [pg 387] rich in the marine treasures of the island have been filled as much by purchase as by personal exertion, there is an absence of the requisite confidence that all professing to be Singhalese have been actually captured in the island and its waters.

The cabinets arranged by the native dealers, though professing to contain the productions of Ceylon, include shells which have been obtained from other islands in the Indian seas; and the information contained in books, probably from these very circumstances, is either obscure or deceptive. The old writers content themselves with assigning to any particular shell the too-comprehensive habitat of "the Indian Ocean," and seldom discriminate between a specimen from Ceylon and one from the Eastern Archipelago or Hindustan. In a very few instances, Ceylon has been indicated with precision as the habitat of particular shells, but even here the views of specific essentials adopted by modern conchologists, and the subdivisions established in consequence, leave us in doubt for which of the described forms the collective locality should be retained.

Valuable notices of Ceylon shells are to be found in detached papers, in periodicals, and in the scientific surveys of exploring voyages. The authentic facts embodied in the monographs of REEVE, KUSTER, SOWERBY, and KIENER, have greatly enlarged our knowledge of the marine testacea; and the land and fresh-water mollusca have been similarly illustrated by the contributions of BENSON and LAYARD to the Annals of Natural History.

The dredge has been used, but only in a few insulated spots along the coasts of Ceylon; European explorers have been rare; and the natives, anxious only to secure the showy and saleable shells of the sea, have neglected [pg 388] the less attractive ones of the land and the lakes. Hence Mr. Hanley finds it necessary to premise that the list appended, although the result of infinite labour and research, is less satisfactory than could have been wished. "It is offered," he says, "with diffidence, not pretending to the merit of completeness as a shell-fauna of the island, but rather as a form, which the zeal of other collectors may hereafter elaborate and fill up."

Looking at the little that has yet been done, compared with the vast and almost untried field which invites explorers, an assiduous collector may quadruple the species hitherto described. The minute shells especially may be said to be unknown; a vigilant examination of the corals and excrescences upon the spondyli and pearl-oysters would signally increase our knowledge of the Rissoæ, Chemnitziæ, and other perforating testacea, whilst the dredge from the deep water will astonish the amateur by the wholly new forms it can scarcely fail to display.

The arrangement here adopted is a modified Lamarckian one, very similar to that used by Reeve and Sowerby, and by Mr. HANLEY, in his Illustrated Catalogue of Recent Shells. 33

[pg 389]A conclusion not unworthy of observation may be deduced from this catalogue; namely, that Ceylon was the unknown, and hence unacknowledged, source of almost every extra-European shell which has been described by Linnæus without a recorded habitat. This fact gives to Ceylon specimens an importance which can only be appreciated by collectors and the students of Mollusca.

The eastern seas are profusely stocked with radiated animals, but it is to be regretted that they have as yet received but little attention from English naturalists. Recently, however, Dr. Kelaart has devoted himself to the investigation of some of the Singhalese species, and has published his discoveries in the Journal of the Ceylon Branch of the Asiatic Society for 1856-8. Our information respecting the radiata on the confines of the island is, therefore, very scanty; with the exception of the genera 95 examined by him. Hence the notice of this extensive class of animals must be limited to indicating a few of those which exhibit striking peculiarities, or which admit of the most common observation.

[pg 396]Star Fish.—Very large species of Ophiuridæ are to be met with at Trincomalie, crawling busily about, and insinuating their long serpentine arms into the irregularities and perforations in the rocks. To these they attach themselves with such a firm grasp, especially when they perceive that they have attracted attention, that it is almost impossible to procure unmutilated specimens without previously depriving them of life, or at least modifying their muscular tenacity. The upper surface is of a dark purple colour, and coarsely spined; the arms of the largest specimens are more than a foot in length, and very fragile.

The star fishes, with immovable rays 96 , are by no means rare; many kinds are brought up in the nets, or maybe extracted from the stomachs of the larger market fish. One very large species 97 , figured by Joinville in the manuscript volume in the library at the India House, is not uncommon; it has thick arms, from which and the disc numerous large fleshy cirrhi of a bright crimson colour project downwards, giving the creature a remarkable aspect. No description of it, so far as I am aware, has appeared in any systematic work on zoology.

Sea Slugs.—There are a few species of Holothuria, of which the trepang is the best known example. It is largely collected in the Gulf of Manaar, and dried in the sun to prepare it for export to China. A good description and figures of its varieties are still desiderata.

Parasitic Worms.—Of these entozoa, the Filaria medinensis, or Guinea-worm, which burrows in the [pg 397] cellular tissue under the skin, is well known in the north of the island, but rarely found in the damper districts of the south and west. In Ceylon, as elsewhere, the natives attribute its occurrence to drinking the waters of particular wells; but this belief is inconsistent with the fact that its lodgment in the human body is almost always effected just above the ankle. This shows that the minute parasites are transferred to the skin of the leg from the moist vegetation bordering the footpaths leading to wells. At this period the creatures are very small, and the process of insinuation is painless and imperceptible. It is only when they attain to considerable size, a foot or more in length, that the operation of extracting them is resorted to, when exercise may have given rise to inconvenience and inflammation.

These pests in all probability received their popular name of Guinea-worms, from the narrative of Bruno or Braun, a citizen and surgeon of Basle, who about the year 1611 made several voyages to that part of the African coast, and on his return published, amongst other things, an account of the local diseases. 98 But Linschoten, the Dutch navigator, had previously observed the same worms at Ormus in 1584, and they are thus described, together with the method of removing them, in the English version of his voyage.

"There is in Ormus a sickenesse or common plague of wormes, which growe in their legges, it is thought that they proceede of the water that they drink. These wormes are like, unto lute strings, and about two or three fadomes longe, which they must plucke out and winde them aboute a straw or a feather, everie day some [pg 398] part thereof, so longe as they feele them creepe; and when they hold still, letting it rest in that sort till the next daye, they bind it fast and annoynt the hole, and the swelling from whence it commeth foorth, with fresh butter, and so in ten or twelve dayes, they winde them out without any let, in the meanetime they must sit still with their legges, for if it should breake, they should not, without great paine get it out of their legge, as I have seen some men doe." 99

The worm is of a whitish colour, sometimes inclining to brown. Its thickness is from a half to two-thirds of a line, and its length has sometimes reached to ten or twelve feet. Small specimens have been found beneath the tunica conjunctiva of the eye; and one species of the same genus of Nematoidea infests the cavity of the eye itself. 100

Planaria.—In the journal already mentioned, Dr. Kelaart has given descriptions of fifteen species of planaria, and four of a new genus, instituted by him for the reception of those differing from the normal kinds by some peculiarities which they exhibit in common. At Point Pedro, Mr. Edgar Layard met with one on the bark of trees, after heavy rain, which would appear to belong to the subgenus geoplana. 101

Acalephæ.—Acalephæ 102 are plentiful, so much so, indeed, that they occasionally tempt the larger cetacea into the Gulf of Manaar. In the calmer months of the year, when the sea is glassy, and for hours together [pg 399] undisturbed by a ripple, the minute descriptions are rendered perceptible by their beautiful prismatic tinting. So great is their transparency that they are only to be distinguished from the water by the return to the eye of the reflected light that glances from their delicate and polished surfaces. Less frequently they are traced by the faint hues of their tiny peduncles, arms, or tentaculæ; and it has been well observed that they often give the seas in which they abound the appearance of being crowded with flakes of half-melted snow. The larger kinds, when undisturbed in their native haunts, attain to considerable size. A faintly blue medusa, nearly a foot across, may be seen in the Gulf of Manaar, where, no doubt, others of still larger growth are to be found.

[pg 400]Occasionally after storms, the beach at Colombo is strewn with the thin transparent globes of the "Portuguese Man of War," Physalus urticulus, which are piled upon the lines left by the waves, like globules of glass delicately tinted with purple and blue. They sting, as their trivial name indicates, like a nettle when incautiously touched.

Red infusoria.—On both sides of the island (but most frequently on the west), during the south-west monsoon, a broad expanse of the sea assumes a red tinge, considerably brighter than brick-dust; and this is confined to a space so distinct that a line seems to separate it from the green water which flows on either side. Observing at Colombo that the whole area so tinged changed its position without parting with any portion of its colouring, I had some of the water brought on shore, and, on examination with the microscope, found it to be filled with infusoria, probably similar to those which have been noticed near the shores of South America, and whose abundance has imparted a name to the "Vermilion Sea" off the coast of California. 103

The remaining orders, including the corals, madrepores, [pg 401] and other polypi, have yet to find a naturalist to undertake their investigation, but in all probability the new species are not very numerous.

The following is the letter of Dr. Grant, referred to at page 385:—

Sir,—I have perused, with much interest, your remarkable communication received yesterday, respecting the musical sounds which you heard proceeding from under water, on the east coast of Ceylon. I cannot parallel the phenomenon you witnessed at Batticaloa, as produced by marine animals, with anything with which my past experience has made me acquainted in marine zoology. Excepting the faint clink of the Tritonia arborescens, repeated only once every minute or two, and apparently produced by the mouth armed with two dense horny laminæ, I am not aware of any sounds produced in the sea by branchiated invertebrata. It is to be regretted that in the memorandum you have not mentioned your observations on the living specimens brought you by the sailors as the animals which produced the sounds. Your authentication of the hitherto unknown fact, would probably lead to the discovery of the same phenomenon in other common accessible paludinæ, and other allied branchiated animals, and to the solution of a problem, which is still to me a mystery, even regarding the tritonia.

My two living tritonia, contained in a large clear colourless glass cylinder, filled with pure sea water, and placed on the central table of the Wernerian Natural History Society of Edinburgh, around which many members were sitting, continued [pg 402] to clink audibly within the distance of twelve feet during the whole meeting. These small animals were individually not half the size of the last joint of my little finger. What effect the mellow sounds of millions of these, covering the shallow bottom of a tranquil estuary, in the silence of night, might produce, I can scarcely conjecture.

In the absence of your authentication, and of all geological explanation of the continuous sounds, and of all source of fallacy from the hum and buzz of living creatures in the air or on the land, or swimming on the waters, I must say that I should be inclined to seek for the source of sounds so audible as those you describe rather among the pulmonated vertebrata, which swarm in the depths of these seas—as fishes, serpents (of which my friend Dr. Cantor has described about twelve species he found in the Bay of Bengal), turtles, palmated birds, pinnipedous and cetaceous mammalia, &c.

The publication of your memorandum in its present form, though not quite satisfactory, will, I think, be eminently calculated to excite useful inquiry into a neglected and curious part of the economy of nature.

I remain, Sir,

Yours most respectfully,

ROBERT E. GRANT.

Sir J. Emerson Tennent, &c. &c.

1Cypræa Argus.

2In one of these beautiful little bays near Catchavelly, between Trincomalie and Batticaloa, I found the sand within the wash of the sea literally covered with mollusca and shells, and amongst others a species of Bullia (B. vittata, I think), the inhabitant of which, has the faculty of mooring itself firmly by sending down its membranous foot into the wet sand, where, imbibing the water, this organ expands horizontally into a broad, fleshy disc, by which the animal anchors itself, and thus secured, collects its food in the ripple of the waves. On the slightest alarm, the water is discharged, the disc collapses into its original dimensions, and the shell and its inhabitant disappear together beneath the sand.

3Ianthina communis, Krause and I. prolongata, Blainv.

4COSMAS INDICO-PLEUSTES, in Thevenot's ed. t i. p. 21.

5At Kottiar, near Trincomalie, I was struck with the prodigious size of the edible oysters, which were brought to us at the rest-house. The shell of one of these measured a little more than eleven inches in length, by half as many broad: thus unexpectedly attesting the correctness of one of the stories related by the historians of Alexander's expedition, that in India they had found oysters a foot long. PLINY says: "In Indico mari Alexandri rerum auctores pedalia inveniri prodidere."—Nat. Hist. lib. xxxii. ch. 31. DARWIN says, that amongst the fossils of Patagonia, he found "a massive gigantic oyster, sometimes even a foot in diameter."—Nat. Voy., ch. viii.

6—ABOUZEYD, Voyages Arabes, &c., t. i. p. 6; REINAUD, Mémoire sur l'Inde, &c p. 222.

7See also the Asiatic Journal for 1827, p. 469.

8DARWIN, in his Naturalist's Voyage, mentions a parallel instance of the localised propagation of colours amoungst the cattle which range the pasturage of East Falkland Island: "Round Mount Osborne about half of some of the herds were mouse-coloured, a tint no common anywhere else,—near Mount Pleasant dark-brown prevailed; whereas south of Choiseul Sound white beasts with black heads and feet were common."—Ch. ix. p. 192.

9It is almost unnecessary to say that the shell fish which produces the true Oriental pearls is not an oyster, but belongs to the genus Avicula, or more correctly, Meleagrina. It is the Meleagrina Margaritifera of Lamarck.

10Cajan is the local term for the plaited fronds of a coco-nut.

11This suspension was in some degree attributable to disputes with the Nabob of Arcot and other chiefs, and the proprietors of temples on the opposite coast of India, who claimed, a right to participate in the fisheries of the Gulf of Manaar.

12"Il y avait autrefois dans le Golfe de Serendyb, une pêcherie de perles qui s'est épuiseé de notre temps. D'un autre côté il s'est formé une pêcherie de Sofala dans le pays des Zends, là ou il n'en existait pas auparavant—on dit que c'est la pêcherie de Serendyb qui s'est transportée à Sofala."—ALBYROUNI, in RENAUD'S Fragmens Arabes, &c, p. 125; see also REINAUD'S Mémoire sur l'Inde, p. 228.

13STEUART'S Pearl Fisheries of Ceylon, p. 27: CORDINER'S Ceylon, &c, vol. ii. p. 45.

14See Dr. KELAART'S Report on the Pearl Oyster in the Ceylon Calendar for 1858—Appendix, p. 14.

15Rapport de M. COSTE, Professeur d'Embryogénie, &c., Paris, 1858.

16Detailed accounts of the pearl fishery of Ceylon and the conduct of the divers, will be found in PERCIVAL's Ceylon, ch. iii.: and in CORDINER'S Ceylon, vol. ii. ch. xvi. There is also a valuable paper on the same subject by Mr. LE BECK, in the Asiatic Researches, vol. v. p. 993; but by far the most able and intelligent description is contained in the Account of the Pearl Fisheries of Ceylon, by JAMES STEUART, Esq., Inspector of the Pearl Banks, 4to. Colombo, 1843.

17MASSOUDI says that the Persian divers, as they could not breathe through their nostrils, cleft the root of the ear for that purpose: "Ils se fendaient la racine de l'oreille pour respirer; en effet, ils ne peuvent se servir pour cet objet des narines, vu qu'ils se les bouchent avec des morceaux d'écailles de tortue marine on bien avec des morceaux de corne ayant la forme d'un fer de lance. En même temps ils se mettent dans l'oreille du coton trempé dans de l'huile."—Moroudj-al-Dzeheb, &c., REINAUD, Mémoire sur l'Inde, p. 228.

18Colonel WILSON says they compress the nose with horn, and close the ears with beeswax. See Memorandum on the Pearl Fisheries in Persian Gulf.—Journ. Geogr. Soc. 1833, vol. iii. p. 283.

19RIBEYRO says that a diver could remain below whilst two credos were being repeated: "Il s'y tient l'espace de deux credo."—Lib. i. ch. xxii. p. 169. PERCIVAL says the usual time for them to be under water was two minutes, but that some divers stayed four or five, and one six minutes,—Ceylon p. 91; LE BECK says that in 1797 he saw a Caffre boy from Karical remain down for the space of seven minutes.—Asiat. Res vol. v. p. 402.

20CORDINER'S Ceylon, vol. ii p. 52.

21"Ils s'enduisaient les pieds et les jambes d'une substance noirâtre, atin de faire peur aux monstres marins, que, sans cela, seraient tentés de les dévorer."—Moroudj-al-Dzekeb, REINAUD, Mém. sur l'Inde, p. 228.

22Along with this two plates are given from drawings made for the Official Inspector, and exhibiting the ascertained size of the pearl oyster at every period of its growth, from the "spat" to the mature shell. The young "brood" are shown at Nos. 1 and 2. The shell at four months old, No. 3, No. 4. six months, No. 5. one year, No. 6, two years. The second plate exhibits the shell at its full growth.

23Report of Dr. KELAART, Oct. 1857.

24Littorina lævis. Cerithium palustre. Of the latter the specimens brought to me were dwarfed and solid, exhibiting in this particular the usual peculiarities that distinguish (1) shells inhabiting a rocky locality from (2) their congeners in a sandy bottom. Their longitudinal development was less, with greater breadth, and increased strength and weight.

25These sounds are thus described by Dr. BUIST in the Bombay Times of January 1847: "A party lately crossing from the promontory in Salsette called the 'Neat's Tongue,' to near Sewree, were, about sunset, struck by hearing long distinct sounds like the protracted booming of a distant bell, the dying cadence of an Æolian harp, the note of a pitchpipe or pitch-fork, or any other long-drawn-out musical note. It was, at first, supposed to be music from Parell floating at intervals on the breeze; then it was perceived to come from all directions, almost in equal strength, and to arise from the surface of the water all around the vessel. The boatmen at once intimated that the sounds were produced by fish, abounding in the muddy creeks and shoals around Bombay and Salsette; they were perfectly well known, and very often heard. Accordingly, on inclining the ear towards the surface of the water; or, better still, by placing it close to the planks of the vessel, the notes appeared loud and distinct, and followed each other in constant succession. The boatmen next day produced specimens of the fish—a creature closely resembling, in size and shape the fresh-water perch of the north of Europe—and spoke of them as plentiful and perfectly well known. It is hoped they may be procured alive, and the means afforded of determining how the musical sounds are produced and emitted, with other particulars of interest supposed new in Ichthyology. We shall be thankful to receive from our readers any information they can give us in regard to a phenomenon which does not appear to have been heretofore noticed, and which cannot fail to attract the attention of the naturalist. Of the perfect accuracy with which the singular facts above related have been given, no doubt will be entertained when it is mentioned that the writer was one of a party of five intelligent persons, by all of whom they were most carefully observed, and the impressions of all of whom in regard to them were uniform. It is supposed that the fish are confined to particular localities—shallows, estuaries, and muddy creeks, rarely visited by Europeans; and that this is the reason why hitherto no mention, so far as we know, has been made of the peculiarity in any work on Natural History."

This communication elicited one from Vizagapatam, relative to "musical sounds like the prolonged notes on the harp" heard to proceed from under water at that station. It appeared in the Bombay Times of Feb. 13, 1849.

26The Cuckoo Gurnard (Triglia cuculus) and the maigre (Sciæna aquila) utter sounds when taken out of the water (YARRELL, vol. i. p. 44, 107); and herrings when the net has just been drawn have been observed to do the same. This effect has been attributed to the escape of air from the air bladder, but no air bladder has been found in the Cottus, which makes a similar noise.

27The fishermen assert that a fish about five inches in length, found in the lake at Colombo, and called by them "magoora," makes a grunt when disturbed under water. PALLEGOIX, in his account of Siam, speaks of a fish resembling a sole, but of brilliant colouring with black spots, which the natives call the "dog's tongue," that attaches itself to the bottom of a boat, "et fait entendre un bruit très-sonore et même harmonieux."—Tom. i. p. 194. A Silurus, found in the Rio Parana, and called the "armado," is remarkable for making a harsh grating noise when caught by hook or line, which can be distinctly heard when the fish is beneath the water. DARWIN, Nat. Journ. ch. vii. Aristotle and Ælian were aware of the existence of this faculty in some of the fishes of the Mediterranean. ARISTOTLE, De Anim., lib. iv. ch. ix.; ÆLIAN, De Nat. Anim., lib. x. ch. xi.; see also PLINY, lib. ix. ch. vii.. lib. xi. ch. cxiii.; ATHENÆUS, lib. vii. ch. iii. vi. I have heard of sounds produced under water at Baltimore, and supposed to be produced by the "cat-fish;" and at Swan River in Australia, where they are ascribed to the "trumpeter." A similar noise heard in the Tagus is attributed by the Lisbon fishermen to the "Corvina"—but what fish is meant by that name, I am unable to tell.

28AGASSIZ, Comparative Physiology, sec. ii. 158.

29It consists of two round vesicles containing fluid, and crystalline or elliptical calcareous particles or otolites, remarkable for their oscillatory action in the living or recently killed animal. OWEN'S Lectures on the Comparative Anatomy and Physiology of the Invertebrate Animals, 1855, p. 511-552.

30I am informed that Professor M&ÜLLER read a paper on "Musical fishes" before the Academy of Berlin, in 1856. It will probably be found in the volume of M&ÜLLER'S Archiv. für Physiologie for that year; but I have not had an opportunity of reading it.

31Edinburgh Philosophical Journ., vol. xiv. p. 188. See also the Appendix to this chapter.

32The letter which I received from Dr. Grant on this subject, I have placed in a note to the present chapter, in the hope that it may stimulate some other inquirer in Ceylon to prosecute the investigation which I was unable to carry out successfully.

33Below will be found a general reference to the Works or Papers in which are given descriptive notices of the shells contained in the following list; the names of the authors (in full or abbreviated) being, as usual, annexed to each species.

ADAMS, Proceed. Zool. Soc. 1853, 54, 56; Thesaur. Conch. ALBERS, Zeitsch. Malakoz. 1853. ANTON, Wiegm. Arch. Nat. 1837; Verzeichn. Conch. BECK in Pfeiffer, Symbol. Helic. BENSON, Ann. Nat. Hist. vii. 1851; xii. 1853, xviii, 1856. BLAINVILLE, Dict. Sc. Nat.; Nouv. Ann. Mus. His. Nat. i. BOLTEN, Mus. BORN, Test. Mus. Cæcs. Vind. BRODERIP, Zool. Journ. i. iii. BRUGUIERE, Encyc. Méthod. Vers. CARPENTER, Proc. Zool. Soc. 1856. CHEMNITZ, Conch. Cab. CHENU, Illus. Conch. DESHAYES. Encyc. Méth. Vers.; Mag. Zool. 1831; Voy. Belanger; Edit. Lam. An. s. Vert.; Proceed. Zool. Soc. 1853, 54, 55. DILLWYN. Deser. Cat. Shells. DOHRN, Proc. Zool. Soc. 1857, 58; Malak. Blätter; Land and Fluviatile Shells of Ceylon. DUCLOS, Monog. of Oliva. FABRICIUS, in Pfeiffer Monog. Helic.; in Dohrn's MSS. FÉRUSSAC, Hist. Mollusques. FORSKAL, Anim. Orient. GMELIN, Syst. Nat. GRAY, Proc. Zool. Soc. 1834, 52; Index Testaceologicus Suppl.; Spicilegia Zool.; Zool. Journ. i.; Zool. Beechey Voy. GRATELOUP, Act. Linn. Bordeaux, xi. GUERIN, Rev. Zool. 1847. HANLEY, Thesaur. Conch, i.; Recent Bivalves; Proc. Zool. Soc. 1858. HINDS, Zool. Voy. Sulphur; Proc. Zool. Soc. HUTTON, Journ. As. Soc. KARSTEN, Mus. Lesk. KIENER, Coquilles Vivantes. KRAUSS, Sud-Afrik Mollusk. LAMARCK, An. sans Vertéb. LAYARD, Proc. Zool. Soc. 1854. LEA, Proceed. Zool. Soc. 1850. LINNÆUS, Syst. Nat. MARTINI, Conch. Cab. MAWE. Introd. Linn. Conch.; Index Test. Suppl. MEUSCHEN, in Gronor. Zoophylac. MENKE, Synop. Mollus. MULLER, Hist. Verm. Terrest. PETIT, Pro. Zool. Soc. 1842. PFEIFFER, Monog. Helic.: Monog. Pneumon.; Proceed. Zool. Soc. 1852, 53, 54, 55. 56; Zeitschr. Malacoz. 1853. PHILIPPI, Zeitsch. Mal. 1846, 47: Abbild. Neuer Conch. POTIEZ et MICHAUD. Galeric Douai. RANG, Mag. Zool. ser. i. p. 100. RÉCLUZ, Proceed. Zool. Soc. 1845; Revue Zool. Cur. 1841: Mag. Conch. REEVE, Conch. Icon.; Proc. Zool. Soc: 1842, 52. SCHUMACHER. Syst. SHUTTLEWORTH. SOLANDER. in Dillwyn's Desc. Cat. Shells; SOWERBY, Genera Shells; Species Conch.; Conch. Misc.; Thesaur. Conch.; Conch. Illus.; Proc. Zool. Soc.; App. to Tankerrille Cat. SPENGLER, Skrivt. Nat. Selsk. Kiobenhav. 1792. SWAINSON, Zool. Illust. ser. ii. TEMPLETON, Ann. Nat. Hist. 1858. TROSCHEL, in Pfeiffer, Mon. Pneum; Zeitschr. Malak. 1847; Wiegm. Arch. Nat. 1837. WOOD, General Conch.

34A. dichotomum, Chenu.

35Fistulana gregata, Lam.

36Blainvillea, Hupé.

37Latraria tellinoides, Lam.

38I have also seen M. hians of Philippi in a Ceylon collection.

39M. Taprobanensis, Index Test. Suppl.

40Psammotella Skinneri, Reeve.

41P. cærulesens, Lam.

42Sanguinolaria rugosa, Lam.

43T. striatula of Lamarck is also supposed to be indigenous to Ceylon.

44T. rostrata, Lam.

45L. divaricata is found, also, in mixed Ceylon collections.

46C. dispar of Chemnitz is occasionally found in Ceylon collections.

47C. impudica. Lam.

48As Donax.

49V. corbis, Lam.

50As Tapes.

51V. textile, Lam.

52?Arca Helblingii, Chemn.

53Mr. Cuming informs me that he has forwarded no less than six distinct Uniones from Ceylon to Isaac Lea, of Philadelphia, for determination or description.

54M. smaragdinus, Chemn.

55As Avicula.

56The specimens are not in a fitting state for positive determination. They are strong, extremely narrow, with the beak of the lower valve much produced, and the inner edge of the upper valve denticulated throughout. The muscular impressions are dusky brown.

57As Anomia.

58The fissurata of Humphreys and Dacosta, pl. 4.—E. rubra, Lamarck.

59B. Ceylanica, Brug.

60P. Tennentii. "Greyish brown, with longitudinal rows of rufous spots, forming interrupted bands along the sides. A singularly handsome species, having similar habits to Limax. Found in the valleys of the Kalany Ganga, near Ruanwellé."—Templeton MSS.

61Not far from bistrialis and Ceylanica. The manuscript species of Mr. Dohrn will shortly appear in his intended work upon the land and fluviatile shells of Ceylon.

62As Ellobium.

63As Melampus.

64As Ophicardelis.

65M. fasciolata, Olivier.

66 66These four species are included on the authority of Mr. Dohrn.

67N. exuvia, Lam. not Linn.

68Conch. Cab. f. 1926-7, and N. melanostoma, Lam. in part.

69Chemn. Conch. Cab. 1892-3.

70N. glauciua, Lam. not Linn.

71A species (possibly Javanicus) is known to have been collected. I have not seen it.

72Not of Lamarck. D. atrata. Reeve.

73Philippia L.

74Zeit. Mal. 1846 for T. argyrostoma, Lam. not Linn.

75Buccinum pyramidatum, Gm. in part: B. sulcatum, var. C. of Brug.

76Teste Cuming.

77As Delphinulat.

78Ed. Lam. Anim. s. Vert.

79P. papyracea, Lam. In mixed collections I have seen the Chinese P. bezoar of Lamarck as from Ceylon.

80P. vespertilio, Gm.

81R. albivaricosa, Reeve.

82M. anguliferus var. Lam.

83T. cynocephalus of Lamarck is also met with in Ceylon collections.

84S. incisus of the Index Testaceologicus (urceus, var. Sow. Thesaur.) is found in mixed Ceylon collections.

85C. plicaria of Lamarck, and C. coronulata of Sowerby, are also said to be found in Ceylon.

86As Purpura.

87N. suturalis, Reeve (as of Lam.), is met with in mixed Ceylon collections.

88E. areolata, Lam.

89E. spirata, Lam. not Linn.

90B. Belangeri, Kiener.

91As Turricula L.

92O. utriculus, Dillwyn.

93C. planorbis, Born; C. vulpinus, Lam.

94Conus ermineus, Born, in part.

95Actinia, 9 sp.; Anthea, 4 sp.; Actinodendron, 3 sp.; Dioscosoma, 1 sp.; Peechea, 1 sp.; Zoanthura, 1 sp.

96Asterias, Linn.

97Pentaceros?

98Footnote 1: In DE BRY'S, Collect, vol. i. p. 49.

99JOHN HUIGHEN VAN LINSCHOTEN his Discours of Voyages into the Easte and West Indies. London, 1599, p, 16.

100OWEN'S Lectures on the Invertebrata, p. 96.

101"A curious species, which is of a light brown above, white underneath; very broad and thin, and has a peculiarly shaped tail, half-moon-shaped in fact, like a grocer's cheese knife."

102Jelly-fish.

103The late Dr. BUIST, of Bombay, in commenting on this statement, writes to the Athenæum that: "The red colour with which the sea is tinged, round the shores of Ceylon, during a part of the S.W. monsoon is due to the Proto-coccus nivalis, or the Himatta-coccus, which presents different colours at different periods of the year—giving us the seas of milk as well as those of blood. The coloured water at times is to be seen all along the coast north to Kurrachee, and far out, and of a much more intense tint in the Arabian Sea. The frequency of its appearance in the Red Sea has conferred on it its name."