THE HORNBILL.

THE HORNBILL.Of the Birds of the island, upwards of three hundred and twenty species have been indicated, for which we are indebted to the persevering labours of Dr. Templeton, Dr. Kelaart, and Mr. Layard; but many yet remain to be identified. In fact, to the eye of a stranger, their prodigious numbers, and especially the myriads of waterfowl which, notwithstanding the presence of the crocodiles, people the lakes and marshes in the eastern provinces, form one of the marvels of Ceylon.

In the glory of their plumage, the birds of the interior are surpassed by those of South America and Northern India; and the melody of their song bears no comparison with that of the warblers of Europe, but the want of brilliancy is compensated by their singular grace of form, and the absence of prolonged and modulated harmony by the rich and melodious tones of their clear and musical calls. In the elevations of the Kandyan country there are a few, such as the robin of Neuera-ellia 1 and the long-tailed thrush 2 , whose song rivals that of their European namesakes; but, far beyond the attraction of their notes, the traveller rejoices in the flute-like voices of the Oriole, the Dayal-bird 3 , [pg 242] and some others equally charming; when at the first dawn of day, they wake the forest with their clear réveil.

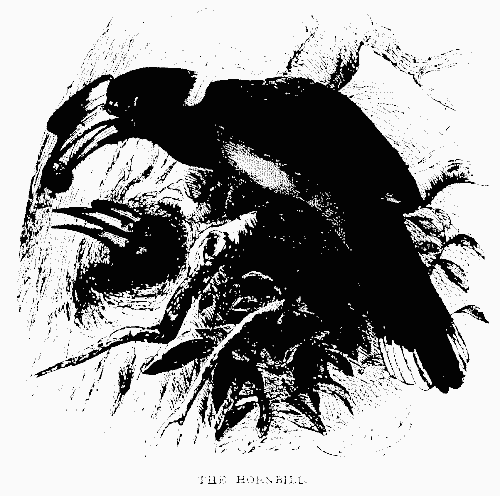

It is only on emerging from the dense woods and coming into the vicinity of the lakes and pasture of the low country, that birds become visible in great quantities. In the close jungle one occasionally hears the call of the copper-smith 4 , or the strokes of the great orange-coloured woodpecker 5 as it beats the decaying trees in search of insects, whilst clinging to the bark with its finely-pointed claws, and leaning for support upon the short stiff feathers of its tail. And on the lofty branches of the higher trees, the hornbill 6 (the toucan of the East), with its enormous double casque, sits to watch the motions of the tiny reptiles and smaller birds on which it preys, tossing them into the air when seized, and catching them in its gigantic mandibles as they fall. 7 The remarkable excrescence on the beak of this [pg 243] extraordinary bird may serve to explain the statement of the Minorite friar Odoric, of Portenau in Friuli, who travelled in Ceylon in the fourteenth century, and brought suspicion on the veracity of his narrative by asserting that he had there seen "birds with two heads." 8

The Singhalese have a belief that the hornbill never resorts to the water to drink; but that it subsists exclusively by what it catches in its prodigious bill while [pg 244] rain is falling. This they allege is associated with the incessant screaming which it keeps up during showers.

As we emerge from the dark shade, and approach park-like openings on the verge of the low country, quantities of pea-fowl are to be found either feeding on the seeds among the long grass or sunning themselves on the branches of the surrounding trees. Nothing to be met with in English demesnes can give an adequate idea of the size and magnificence of this matchless bird when seen in his native solitudes. Here he generally selects some projecting branch, from which his plumage may hang free of the foliage, and, if there be a dead and leafless bough, he is certain to choose it for his resting-place, whence he droops his wings and suspends his gorgeous train, or spreads it in the morning sun to drive off the damps and dews of the night.

In some of the unfrequented portions of the eastern province, to which Europeans rarely resort, and where the pea-fowl are unmolested by the natives, their number is so extraordinary that, regarded as game, it ceases to be "sport" to destroy them; and their cries at early dawn are so tumultuous and incessant as to banish sleep, and amount to an actual inconvenience. Their flesh is excellent in flavour when served up hot, though it is said to be indigestible; but, when cold, it contracts a reddish and disagreeable tinge.

The European fable of the jackdaw borrowing the plumage of the peacock, has its counterpart in Ceylon, where the popular legend runs that the pea-fowl stole the plumage of a bird called by the natives avitchia. I have not been able to identify the species which bears [pg 245] this name; but it utters a cry resembling the word matkiang! which in Singhalese means, "I will complain!" This they believe is addressed by the bird to the rising sun, imploring redress for its wrongs. The avitchia is described as somewhat less than a crow, the colours of its plumage being green, mingled with red.

But of all, the most astonishing in point of multitude, as well as the most interesting from their endless variety, are the myriads of aquatic birds and waders which frequent the lakes and watercourses; especially those along the coast near Batticaloa, between the mainland and the sand formations of the shore, and the innumerable salt marshes and lagoons to the south of Trincomalie. These, and the profusion of perching birds, fly-catchers, finches, and thrushes, that appear in the open country, afford sufficient quarry for the raptorial and predatory species—eagles, hawks, and falcons—whose daring sweeps and effortless undulations are striking objects in the cloudless sky.

I. ACCIPITRES. Eagles.—The Eagles, however, are small, and as compared with other countries rare; except, perhaps, the crested eagle 9 , which haunts the mountain provinces and the lower hills, disquieting the peasantry by its ravages amongst their poultry; and the gloomy serpent eagle 10 , which, descending from its eyrie in the lofty jungle, and uttering a loud and plaintive cry, sweeps cautiously around the lonely tanks and marshes, to feed upon the reptiles on their margin. The largest eagle is the great sea Erne 11 , seen on the [pg 246] northern coasts and the salt lakes of the eastern provinces, particularly when the receding tide leaves bare an expanse of beach, over which it hunts, in company with the fishing eagle 12 , sacred to Siva. Unlike its companions, however, the sea eagle rejects garbage for living prey, and especially for the sea snakes which abound on the northern coasts. These it seizes by descending with its wings half closed, and, suddenly darting down its talons, it soars aloft again with its writhing victim. 13

Hawks.—The beautiful Peregrine Falcon 14 is rare, but the Kestrel 15 is found almost universally; and the bold and daring Goshawk 16 wherever wild crags and precipices afford safe breeding places. In the district of Anarajapoora, where it is trained for hawking, it is usual, in lieu of a hood, to darken its eyes by means of a silken thread passed through holes in the eyelids. The ignoble birds of prey, the Kites 17 , keep close by the shore, and hover round the returning boats of the fishermen to feast on the fry rejected from their nets.

Owls.—Of the nocturnal accipitres the most remarkable is the brown owl, which, from its hideous yell, has acquired the name of the "Devil-Bird." 18 The Singhalese [pg 247] regard it literally with horror, and its scream by night in the vicinity of a village is bewailed as the harbinger of impending calamity. 19 There is a popular legend in connection with it, to the effect that a morose [pg 248] and savage husband, who suspected the fidelity of his wife, availed himself of her absence to kill her child, of whose paternity he was doubtful, and on her return placed before her a curry prepared from its flesh. Of this the unhappy woman partook, till discovering the crime by finding the finger of her infant, she fled in frenzy to the forest, and there destroyed herself. On her death she was metamorphosed, according to the Buddhist belief, into an ulama, or Devil-bird, which still at nightfall horrifies the villagers by repeating the frantic screams of the bereaved mother in her agony.

II. PASSERES. Swallows.—Within thirty-five miles of Caltura, on the western coast, are inland caves, to which the Esculent Swift 20 resorts, and there builds the "edible bird's nest," so highly prized in China. Near the spot a few Chinese immigrants have established themselves, who rent the nests as a royalty from the government, and make an annual export of the produce. But the Swifts are not confined to this district, and caves containing [pg 249] them have been found far in the interior, a fact which complicates the still unexplained mystery of the composition of their nest; and, notwithstanding the power of wing possessed by these birds, adds something to the difficulty of believing that it consists of glutinous material obtained from algæ. 21 In the nests brought to me there was no trace of organisation; and the original material, whatever it be, is so elaborated by the swallow as to present somewhat the appearance and consistency of strings of isinglass. The quantity of these nests exported from Ceylon is trifling.

Kingfishers.—In solitary places, where no sound breaks the silence except the gurgle of the river as it sweeps round the rocks, the lonely Kingfisher, the emblem of vigilance and patience, sits upon an overhanging branch, his turquoise plumage hardly less intense in its lustre than the deep blue of the sky above him; and so intent is his watch upon the passing fish that intrusion fails to scare him from his post.

Sun Birds.—In the gardens the tiny Sun Birds 22 (known as the Humming Birds of Ceylon) hover all day long, attracted to the plants, over which they hang poised on their glittering wings, and inserting their curved beaks to extract the insects that nestle in the flowers.

Perhaps the most graceful of the birds of Ceylon in form and motions, and the most chaste in colouring, is the one which Europeans call "the Bird of Paradise," 23 and [pg 250] natives "the Cotton Thief," from the circumstance that its tail consists of two long white feathers, which stream behind it as it flies. Mr. Layard says:—"I have often watched them, when seeking their insect prey, turn suddenly on their perch and whisk their long tails with a jerk over the bough, as if to protect them from injury."

The tail is sometimes brown, and the natives have the idea that the bird changes its plumage at stated periods, and that the tail-feathers become white and brown in alternate years. The fact of the variety of plumage is no doubt true, but this story as to the alternation [pg 251] of colours in the same individual requires confirmation. 24

The Bulbul.—The Condatchee Bulbul 25 , which, from the crest on its head, is called by the Singhalese the "Konda Cooroola," or Tuft bird, is regarded by the natives as the most "game" of all birds; and training it to fight was one of the duties entrusted by the Kings of Kandy to the Cooroowa, or Head-man, who had charge of the King's animals and Birds. For this purpose the Bulbul is taken from the nest as soon as the sex is distinguishable by the tufted crown; and secured by a string, is taught to fly from hand to hand of its keeper. When pitted against an antagonist, such is the obstinate courage of this little creature that it will sink from exhaustion rather than release its hold. This propensity, and the ordinary character of its notes, render it impossible that the Bulbul of India could be identical with the Bulbul of Iran, the "Bird of a Thousand Songs," 26 of which, poets say that its delicate passion for the rose gives a plaintive character to its note.

Tailor-Bird.—The Weaver-Bird.—The tailor-bird 27 having completed her nest, sewing together leaves by passing through them a cotton thread twisted by herself, leaps from branch to branch to testify her happiness by [pg 252] a clear and merry note; and the Indian weaver 28 , a still more ingenious artist, hangs its pendulous dwelling from a projecting bough; twisting it with grass into a form somewhat resembling a bottle with a prolonged neck, the entrance being inverted, so as to baffle the approaches of its enemies, the tree snakes and other reptiles. The natives assert that the male bird carries fire flies to the nest, and fastens them to its sides by a particle of soft mud;—Mr. Layard assures me that although he has never succeeded in finding the fire fly, the nest of the male bird (for the female occupies another during incubation) invariably contains a patch [pg 253] of mud on each side of the perch. Grass is apparently the most convenient material for the purposes of the Weaver-bird when constructing its nest, but other substances are often substituted, and some nests which I brought from Ceylon proved to be formed with delicate strips from the fronds of the dwarf date-palm, Phoenix paludosa, which happened to grow near the breeding place.

Amongst the birds of this order, one which, as far as I know, is peculiar to the island is Layard's Mountain-jay (Cissa puella, Blyth and Layard), is distinguished not less by the beautiful blue colour which enlivens its plumage, than by the elegance of its form and the grace of its attitudes. It frequents the hill country, and is found about the mountain streams at Neuera-ellia, and elsewhere. 29

Crows.—Of all the Ceylon birds of this order the most familiar and notorious are the small glossy crows, whose shining black plumage shot with blue has suggested the title of Corvus splendens. 30 They frequent the towns in companies, and domesticate themselves in the close vicinity of every house; and it may possibly serve to account for the familiarity and audacity which they exhibit in their intercourse with men, that the Dutch during their sovereignty in Ceylon, enforced severe penalties against any one killing a crow, under the belief that they were instrumental in extending the [pg 254] growth of cinnamon by feeding on the fruit, and thus disseminating the undigested seed. 31

So accustomed are the natives to their presence and exploits, that, like the Greeks and Romans, they have made the movements of crows the basis of their auguries; and there is no end to the vicissitudes of good and evil fortune which may not be predicted from the direction of their flight, the hoarse or mellow notes of their croaking, the variety of trees on which they rest, and the numbers in which they are seen to assemble.

All day long these birds are engaged in watching either the offal of the offices, or the preparation for meals in the dining-room: and as doors and windows are necessarily opened to relieve the heat, nothing is more common than the passage of a crow across the room, lifting on the wing some ill-guarded morsel from the dinner-table. No article, however unpromising its quality, provided only it be portable, can with safety be left unguarded in any apartment accessible to them. The contents of ladies' work-boxes, kid gloves, and pocket handkerchiefs vanish instantly if exposed near a window or open door. They open paper parcels to ascertain the contents; they will undo the knot on a napkin if it encloses anything eatable, and I have known a crow to extract the peg which fastened the lid of a basket in order to plunder the provender within.

On one occasion a nurse seated in a garden adjoining a regimental mess-room, was terrified by seeing a bloody clasp-knife drop from the air at her feet; but the mystery was explained on learning that a crow, which had been watching the cook chopping mince-meat, had seized [pg 255] the moment when his head was turned to carry off the knife.

One of these ingenious marauders, after vainly attitudinising in front of a chained watch-dog, that was lazily gnawing a bone, and after fruitlessly endeavouring to divert his attention by dancing before him, with head awry and eye askance, at length flew away for a moment, and returned bringing a companion which perched itself on a branch a few yards in the rear. The crow's grimaces were now actively renewed, but with no better success, till its confederate, poising itself on its wings, descended with the utmost velocity, striking the dog upon the spine with all the force of its strong beak. The ruse was successful; the dog started with surprise and pain, but not quickly enough to seize his assailant, whilst the bone he had been gnawing was snatched away by the first crow the instant his head was turned. Two well-authenticated instances of the recurrence of this device came within my knowledge at Colombo, and attest the sagacity and powers of communication and combination possessed by these astute and courageous birds.

On the approach of evening the crows near Colombo assemble in noisy groups along the margin of the freshwater lake which surrounds the fort on the eastern side; and here for an hour or two they enjoy the luxury of throwing the water over their shining backs, and arranging their plumage decorously, after which they disperse, each taking the direction of his accustomed quarters for the night. 32

[pg 256]During the storms which usher in the monsoon, it has been observed, that when coco-nut palms are destroyed by lightning, the effect frequently extends beyond a single tree, and from the contiguity and conduction of the spreading leaves, or some other peculiar cause, large groups will be affected by a single flash, a few killed instantly, and the rest doomed to rapid decay. In Belligam Bay, a little to the east of Point-de-Galle, a small island, which is covered with coco-nuts, has acquired the name of "Crow Island," from being the resort of those birds, which are seen hastening towards it in thousands towards sunset. A few years ago, during a violent storm of thunder, such was the destruction of the crows that the beach for some distance was covered with a black line of their remains, and the grove on which they had been resting was to a great extent destroyed by the same flash. 33

III. SCANSORES. Parroquets.—Of the Psittacidæ the only examples are the parroquets, of which the most renowned is the Palæornis Alexandri, which has the historic distinction of bearing the name of the great conqueror of India, having been the first of its race introduced to the knowledge of Europe on the return of his expedition. An idea of their number may be formed from the following statement of Mr. Layard, as to the multitudes which are to be found on the western coast. "At Chilaw, I have seen such vast flights of parroquets hurrying towards the coco-nut trees which overhang the [pg 257] bazaar, that their noise drowned the Babel of tongues bargaining for the evening provisions. Hearing of the swarms that resorted to this spot, I posted myself on a bridge some half mile distant, and attempted to count the flocks which came from a single direction to the eastward. About four o'clock in the afternoon, straggling parties began to wend towards home, and in the course of half an hour the current fairly set in. But I soon found that I had no longer distinct flocks to count, it became one living screaming stream. Some flew high in the air till right above their homes, and dived abruptly downward with many evolutions till on a level with the trees; others kept along the ground and dashed close by my face with the rapidity of thought, their brilliant plumage shining with an exquisite lustre in the sun-light. I waited on the spot till the evening closed, when I could hear, though no longer distinguish, the birds fighting for their perches, and on firing a shot they rose with a noise like the 'rushing of a mighty wind,' but soon settled again, and such a din commenced as I shall never forget; the shrill screams of the birds, the fluttering of their innumerable wings, and the rustling of the leaves of the palm trees was almost deafening, and I was glad at last to escape to the Government Rest House." 34

IV. COLUMBIDÆ. Pigeons.—Of pigeons and doves there are at least a dozen species. Some live entirely on trees 35 , never alighting on the ground; others, notwithstanding the abundance of food and warmth, are [pg 258] migratory 36 , allured, as the Singhalese allege, by the ripening of the cinnamon berries, and hence one species is known in the southern provinces as the "Cinnamon Dove." Others feed on the fruits of the banyan: and it is probably to their instrumentality that this marvellous tree chiefly owes its diffusion, its seeds being carried by them to remote localities. A very beautiful pigeon, peculiar to the mountain range, discovered in the lofty trees at Neuera-ellia, has, in compliment to the Viscountess Torrington, been named Carpophaga Torringtoniæ.

Another, called by the natives neela-cobeya 37 , although strikingly elegant both in shape and colour, is still more remarkable for the singularly soothing effect of its low and harmonious voice. A gentleman who has spent many years in the jungle, in writing to me of this bird and of the effects of its melodious song, says, that "its soft and melancholy notes, as they came from some solitary place in the forest, were the most gentle sounds I ever listened to. Some sentimental smokers assert that the influence of the propensity is to make them feel as if they could freely forgive all who had ever offended them; and I can say with truth such has been the effect on my own nerves of the plaintive murmurs of the neela-cobeya, that sometimes, when irritated, and not without reason, by the perverseness of some of my native followers, the feeling has almost instantly subsided into placidity on suddenly hearing the loving tones of these beautiful birds."

[pg 259]V. GALLINÆ. The Ceylon Jungle-fowl.—The jungle-fowl of Ceylon 38 is shown by the peculiarity of its plumage to be not only distinct from the Indian species, but peculiar to the island. It has never yet bred or survived long in captivity, and no living specimens have been successfully transmitted to Europe. It abounds in all parts of the island, but chiefly in the lower ranges of mountains; and one of the vivid memorials which are associated with our journeys through the hills, is its clear cry, which sounds like a person calling "George Joyce," 39 and rises at early morning amidst mist and dew, giving life to the scenery, that has scarcely yet been touched by the sun-light.

The female of this handsome bird was figured many years ago by Dr. GRAY in his illustrations of "Indian Zoology," under the name of G. Stanleyi. The cock bird subsequently received from LESSON, the name by which the species is now known: but its habitat was not discovered, until a specimen having been forwarded from Ceylon to Calcutta, Dr. BLYTH recognised it as the long-sought-for male of Dr. Gray's specimen.

Another of the Gallinæ of Ceylon, remarkable for the delicate pencillings of its plumage, as well as for the peculiarity of the double spur, from which it has acquired its trivial name, is the Galloperdix bicalcaratus, of which a figure is given from a drawing by Mr. Gould.

[pg 260]VI. GRALLÆ.—On reaching the marshy plains and shallow lagoons on either side of the island, the astonishment of the stranger is excited by the endless multitudes of stilt-birds and waders which stand in long array within the wash of the water, or sweep in vast clouds above it. Ibises 40 , storks 41 , egrets, spoonbills 42 , herons 43 , and the smaller races of sand larks and plovers, are seen busily traversing the wet sand, in search of the red worm which burrows there, or peering with steady eye to watch the motions of the small fry and aquatic insects in the ripple on the shore.

VII. ANSERES.—Preeminent in size and beauty, the [pg 261] tall flamingoes 44 , with rose-coloured plumage, line the beach in long files. The Singhalese have been led, from their colour and their military order, to designate them the "English Soldier birds." Nothing can be more startling than the sudden flight of these splendid creatures when alarmed; their strong wings beating the air with a sound like distant thunder; and as they soar over head, the flock which appeared almost white but a moment before, is converted into crimson by the sudden display of the red lining of their wings. A peculiarity in the beak of this bird has scarcely attracted the attention it merits, as a striking illustration of creative wisdom in adapting the organs of animals to their local necessities.

[pg 262]The upper mandible, which is convex in other birds, is flattened in the flamingo, whilst the lower, instead of being flat, is convex. To those who have had an opportunity of witnessing the action of the bird in its native haunts, the expediency of this arrangement is at once apparent. To counteract the extraordinary length of its legs, it is provided with a proportionately long neck, so that in feeding in shallow water the crown of the head becomes inverted and the upper mandible brought into contact with the bottom; where its flattened surface qualifies it for performing the functions of the lower one in birds of the same class; and the edges of both being laminated, it is thus enabled, like the duck, by the aid of its fleshy tongue, to sift before swallowing its food.

Floating on the surface of the deeper water, are fleets of the Anatidæ, the Coromandel teal 45 , the Indian hooded gull 46 , the Caspian tern, and a countless variety of ducks and smaller fowl—pintails 47 , teal 48 , red-crested pochards 49 , shovellers 50 , and terns. 51 Pelicans 52 in great numbers resort to the mouths of the rivers, taking up their position at sunrise on some projecting rock, from which to dart on the passing fish, and returning far inland at night to their retreats among the trees, which overshadow some solitary river or deserted tank.

I chanced upon one occasion to come unexpectedly upon one of these remarkable breeding places during a visit which I made to the great tank of Padivil, one of those gigantic constructions by which the early kings of Ceylon have left imperishable records of their reigns.

[pg 263]It is situated in the depth of the forests to the north-west of Trincomalie; and the tank is itself the basin of a broad and shallow valley, enclosed between two lines of low hills, that gradually sink into the plain as they approach towards the sea. The extreme breadth of the included space may be twelve or fourteen miles, narrowing to eleven at the spot where the retaining bund has been constructed across the valley; and when this enormous embankment was in effectual repair, and the reservoir filled by the rains, the water must have been thrown back along the basin of the valley for at least fifteen miles. It is difficult now to determine the precise distances, as the overgrowth of wood and jungle has obliterated all lines left by the original level of the lake at its junction with the forest. Even when we rode along it, the centre of the tank was deeply submerged, so that notwithstanding the partial escape, the water still covered an area of ten miles in diameter. Even now its depth when full must be very considerable, for high on the branches of the trees that grow in the area, the last flood had left quantities of driftwood and withered grass; and the rocks and banks were coated with the yeasty foam, that remains after the subsidence of an agitated flood.

The bed of the tank was difficult to ride over, being still soft and treacherous, although covered everywhere with tall and waving grass; and in every direction it was poched into deep holes by the innumerable elephants that had congregated to roll in the soft mud, to bathe in the collected water, or to luxuriate in the rich herbage, under the cool shade of the trees. The ground, too, was thrown up into hummocks like great molehills which, the natives told us, were formed by a huge earthworm, [pg 264] common in Ceylon, nearly two feet in length, and as thick as a small snake. Through these inequalities the water was still running off in natural drains towards the great channel in the centre, that conducts it to the broken sluice; and across these it was sometimes difficult to find a safe footing for our horses.

In a lonely spot, towards the very centre of the tank, we came unexpectedly upon an extraordinary scene. A sheet of still water, two or three hundred yards broad, and about half a mile long, was surrounded by a line of tall forest-trees, whose branches stretched above its margin. The sun had not yet risen, when we perceived some white objects in large numbers on the tops of the trees; and as we came nearer, we discovered that a vast colony of pelicans had formed their settlement and breeding-place in this solitary retreat. They literally covered the trees in hundreds; and their heavy nests, like those of the swan, constructed of large sticks, forming great platforms, were sustained by the horizontal branches. Each nest contained three eggs, rather larger than those of a goose; and the male bird stood placidly beside the female as she sat upon them.

Nor was this all; along with the pelicans prodigious numbers of other water-birds had selected this for their dwelling-place, and covered the trees in thousands, standing on the topmost branches; tall flamingoes, herons, egrets, storks, ibises, and other waders. We had disturbed them thus early, before their habitual hour for betaking themselves to their fishing-fields. By degrees, as the light increased, we saw them beginning to move upon the trees; they looked around them on every side, stretched their awkward legs behind them, extended their broad wings, gradually rose in groups, [pg 265] and slowly soared away in the direction of the seashore.

The pelicans were apparently later in their movements; they allowed us to approach as near them as the swampy nature of the soil would permit; and even when a gun was discharged amongst them, only those moved off which the particles of shot disturbed. They were in such numbers at this favourite place; that the water over which they had taken up their residence was swarming with crocodiles, attracted by the frequent fall of the young birds; and the natives refused, from fear of them, to wade in for one of the larger pelicans which had fallen, struck by a rifle ball. It was altogether a very remarkable sight.

Of the birds familiar to European sportsmen, partridges and quails are to be had at all times; the woodcock has occasionally been shot in the hills, and the ubiquitous snipe, which arrives in September from Southern India, is identified not alone by the eccentricity of its flight, but by retaining in high perfection the qualities which have endeared it to the gastronome at home. But the magnificent pheasants, which inhabit the Himalayan range and the woody hills of the Chin-Indian peninsula, have no representative amongst the tribes that people the woods of Ceylon; although a bird believed to be a pheasant has more than once been seen in the jungle, close to Rangbodde, on the road to Neuera-ellia.

In submitting this Catalogue of the birds of Ceylon, I am anxious to state that the copious mass of its contents [pg 266] is mainly due to the untiring energy and exertions of my friend, Mr. E.L. Layard. Nearly every bird in the list has fallen by his gun; so that the most ample facilities have been thus provided, not only for extending the limited amount of knowledge which formerly existed on this branch of the zoology of the island; but for correcting, by actual comparison with recent specimens, the errors which had previously prevailed as to imperfectly described species. The whole of Mr. Layard's fine collection is at present in England.

The following is a list of the birds which are, as far as is at present known, peculiar to the island; it will probably be determined at some future day that some included in it have a wider geographical range.

Hæmatornis spilogaster. The "Ceylon eagle;" was discovered by Mr. Layard in the Wanny, and by Dr. Kelaart at Trincomalie.

Athene castonotus. The chestnut-winged hawk owl. This pretty little owl was added to the list of Ceylon birds by Dr. Templeton. Mr. Blyth is at present of opinion that this bird is identical with Ath. Castanopterus, Horsf. of Java as figured by Temminck: P. Col.

Batrachostomus moniliger. The oil bird; was discovered amongst the precipitous rocks of the Adam's Peak range by Mr. Layard. Another specimen was sent about the same time to Sir James Emerson Tennent from Avisavelle. Mr. Mitford has met with it at Ratnapoora.

Caprimulgus Kelaarti. Kelaart's nightjar; swarms on the marshy plains of Neuera-ellia at dusk.

Hirundo hyperythra. The red-bellied swallow; was discovered in 1849, by Mr. Layard at Ambepusse. They build a globular nest, with a round hole at top. A pair built in the ring for a hanging lamp in Dr. Gardner's study at Peradenia, and hatched their young, undisturbed by the daily trimming and lighting of the lamp.

Cisticola omalura. Layard's mountain grass warbler; is found in abundance on Horton Plain and Neuera-ellia, among the long Patena grass.

Drymoica valida. Layard's wren-warbler; frequents tufts of grass and low bushes, feeding on insects.

Pratincola atrata. The Neuera-ellia robin; a melodious songster; added to our catalogue by Dr. Kelaart.

Brachypteryx Palliseri. Ant thrush. A rare bird, added by Dr. Kelaart from Dimboola and Neuera-ellia.

Pellorneum fuscocapillum. Mr. Layard found two specimens of this rare thrush creeping about shrubs and bushes, feeding on insects.

Alcippe nigrifrons. This thrush frequents low impenetrable thickets, and seems to be widely distributed.

Oreocincla spiloptera. The spotted thrush is only found in the mountain zone about lofty trees.

Merula Kinnisii. The Neuera-ellia blackbird; was added by Dr. Kelaart.

Garrulax cinereifrons. The ashy-headed babbler; was found by Mr. Layard near Ratnapoora.

Pomatorhinus melanurus. Mr. Layard states that the mountain babbler frequents low, scraggy, impenetrable brush, along the margins of deserted cheena land. This may turn out to be little more than a local yet striking variety of P. Horsfieldii of the Indian Peninsula.

Malacocercus rufescens. The red dung thrush added by Dr. Templeton to the Singhalese Fauna, is found in thick jungle in the southern and midland districts.

Pycnonotus penicillatus. The yellow-eared bulbul; was found by Dr. Kelaart at Neuera-ellia.

Butalis Muttui. This very handsome flycatcher was procured at Point Pedro, by Mr. Layard.

Dicrurus edoliformis. Dr. Templeton found this kingcrow at the Bibloo Oya. Mr. Layard has since got it at Ambogammoa.

Dicrurus leucopygialis. The Ceylon kingcrow was sent to Mr. Blyth from the vicinity of Colombo, by Dr. Templeton. A species very closely allied to D. coerulescens of the Indian continent.

Tephrodornis affinis. The Ceylon butcher-bird. A migatory species found in the wooded grass lands in October.

Cissa puella. Layard's mountain jay. A most lovely bird, found along mountain streams at Neuera-ellia and elsewhere.

Eulabes ptilogenys. Templeton's mynah. The largest and most beautiful of the species. It is found in flocks perching on the highest trees, feeding on berries.

Munia Kelaarti. This Grosbeak previously assumed to be M. pectoralls of Jerdon; is most probably peculiar to Ceylon.

Loriculus asiaticus. The small parroquet, abundant in various districts.

Palæornis Calthropæ. Layard's purple-headed parroquet, found at Kandy, is a very handsome bird, flying in flocks, and resting on the summits of the very highest trees. Dr. Kelaart states that it is the only parroquet of the Neuera-ellia range.

Megalaima flavifrons. The yellow-headed barbet, is not uncommon.

Megalaima rubricapilla, is found in most parts of the island.

[pg 270]Picus gymnophthalmus. Layard's woodpecker. The smallest of the species, was discovered near Colombo, amongst jak-trees.

Brachypternus Ceylonus. The Ceylon woodpecker, is found in abundance near Neuera-ellia.

Brachypternus rubescens. The red woodpecker.

Centropus chlororhynchus. The yellow-billed cuckoo, was detected by Mr. Layard in dense jungle near Colombo and Avisavelle.

Phoenicophaus pyrrhocephalus. The malkoha, is confined to the southern highlands.

Treron Pompadoura. The Pompadour pigeon. "The Prince of Canino has shown that this is a totally distinct bird from Tr. flavogularis, with which it was confounded: it is much smaller, with the quantity of maroon colour on the mantle greatly reduced."—Paper by Mr. BLYTH, Mag. Nat. Hist. p. 514: 1857.

Carpophaga Torringtoniæ. Lady Torrington's pigeon; a very handsome pigeon discovered in the highlands by Dr. Kelaart. It flies high in long sweeps, and makes its nest on the loftiest trees. Mr. Blyth is of opinion that it is no more than a local race, barely separable from C. Elphinstonii of the Nilgiris and Malabar coast.

Carpophaga pusilla. The little-hill dove a migratory species found by Mr. Layard in the mountain zone, only appearing with the ripened fruit of the teak, banyan, &c., on which they feed.

Gallus Lafayetti.—The Ceylon jungle fowl. The female of this handsome bird was figured by Mr. GRAY (Ill. Ind. Zool.) under the name of G. Stanleyi. The cock bird had long been lost to naturalists, until a specimen was forwarded by Dr. Templeton to Mr. Blyth, who at once recognised it as the long-looked-for male of Mr. Gray's recently described female. It is abundant in all the uncultivated portions of Ceylon; coming out into the open spaces to feed in the mornings and evenings. Mr. Blyth states that there can be no doubt that Hardwicke's published figure refers to the hen of this species, long afterwards termed G. Lafayetti.

Galloperdix bicalcaratus. Not uncommon in suitable situations.

[pg 271]1Pratincola atrata, Kelaart.

2Kittacincla macrura, Gm.

3Copsychussaularis, Linn.. Called by the Europeans in Ceylon the "Magpie Robin." This is not to be confounded with the other popular favourite the "Indian Robin" (Thamnobia fulicata, Linn.), which is "never seen in the unfrequented jungle, but, like the coco-nut palm, which the Singhalese assert will only flourish within the sound of the human voice, it is always found near the habitations of men."—E.L. LAYARD.

4The greater red-headed Barbet (Megalaima indica, Lath.; M. Philippensis, var. A. Lath.), the incessant din of which resembles the blows of a smith hammering a cauldron.

5Brachypternus aurantius, Linn.

6Buceros pica, Scop.; B. Malaharicus, Jerd. The natives assert that B. pica builds in holes in the trees, and that when incubation has fairly commenced, the female takes her seat on the eggs, and the male closes up the orifice by which she entered, leaving only a small aperture through which he feeds his partner, whilst she successfully guards their treasures from the monkey tribes; her formidable bill nearly filling the entire entrance. See a paper by Edgar L. Layard, Esq. Mag. Nat. Hist. March, 1853. Dr. Horsfield had previously observed the same habit in a species of Buceros in Java. (See HORSFIELD and MOORE'S Catal. Birds, E.I. Comp. Mus. vol. ii.) It is curious that a similar trait, though necessarily from very different instincts, is exhibited by the termites, who literally build a cell round the great progenitrix of the community, and feed her through apertures.

7The hornbill is also frugivorous, and the natives assert that when endeavouring to detach a fruit, if the stem is too tough to be severed by his mandibles, he flings himself off the branch so as to add the weight of his body to the pressure of his beak. The hornbill abounds in Cuttack, and bears there the name of "Kuchila-Kai," or Kuchila-eater, from its partiality for the fruit of the Strychnus nuxvomica. The natives regard its flesh as a sovereign specific for rheumatic affections.—Asiat. Res. ch. xv. p. 184.

8Itinerarius FRATRIS ODORICI, de Foro Julii de Portu-vahonis, &c.—HAKLUYT, vol. ii. p. 39.

9Spizaëtuslimnaëtus, Horsf. The race of these birds in the Deccan and Ceylon are rather more crested, originating the Sp. Cristatellus, Auct.

10Which Gould believes to be the Hæmatornis Bacha, Daud.

11Pontoaëtus leucogaster, Gmel.

12Haliastur Indus, Bodd.

13E.L. Layard. Europeans have given this bird the name of the "Brahminy Kite," probably from observing the superstitious feeling of the natives regarding it, who believe that when two armies are about to engage, its appearance prognosticates victory to the party over whom it hovers.

14Falco peregrinus, Linn.

15Tinnunculus alaudarius, Briss.

16Astur trivirgatus, Temm.

17Milvus govinda, Sykes. Dr. Hamilton Buchanan remarks that when gorged this bird delights to sit on the entablature of buildings, exposing its back to the hottest rays of the sun, placing its breast against the wall, and stretching out its wings exactly as the Egyptian Hawk is represented on the monuments.

18Syrnium Indranee, Sykes. Mr. Blyth writes to me from Calcutta that there are some doubts about this bird. There would appear to be three or four distinguishable races, the Ceylon bird approximating most nearly to that of the Malayan Peninsula.

19The horror of this nocturnal scream was equally prevalent in the West as in the East. Ovid introduces it in his Fasti, L. vi. l. 139; and Tibullus in his Elegies, L. i. El. 5. Statius says—

Nocturnæque gemunt striges, et feralla bubo

Damna canens. Theb. iii. l. 511.

But Pliny, l. xi. c. 93, doubts as to what bird produced the sound;—and the details of Ovid's description do not apply to an owl.

Mr. Mitford, of the Ceylon Civil Service, to whom I am indebted for many valuable notes relative to the birds of the island, regards the identification of the Singhalese Devil-Bird as open to similar doubt: he says—"The Devil-Bird is not an owl. I never heard it until I came to Kornegalle, where it haunts the rocky hill at the back of Government-house. Its ordinary note is a magnificent clear shout like that of a human being, and which can be heard at a great distance, and has a fine effect in the silence of the closing night. It has another cry like that of a hen just caught, but the sounds which have earned for it its bad name, and which I have heard but once to perfection, are indescribable, the most appalling that can be imagined, and scarcely to be heard without shuddering; I can only compare it to a boy in torture, whose screams are being stopped by being strangled. I have offered rewards for a specimen, but without success. The only European who had seen and fired at one agreed with the natives that it is of the size of a pigeon, with a long tail. I believe it is a Podargus or Night Hawk." In a subsequent note he further says—"I have since seen two birds by moonlight, one of the size and shape of a cuckoo, the other a large black bird, which I imagine to be the one which gives these calls."

20Collocalia brevirostris, McClell.; C. nidifica, Gray.

21An epitome of what has been written on this subject will be found in Dr. Horsfield's Catalogue of the Birds in the E.I. Comp. Museum, vol. i. p. 101, &c. Mr. Morris assures me, that he has found the nests of the Esculent Swallow eighty miles distant from the sea.

22Nectarina Zeylanica, Linn.

23Tchitrea paradisi, Linn.

24The engraving of the Tchitrea given on page 244 is copied by permission from one of the splendid drawings in. MR. GOULD'S Birds of India.

25Pycnonotus hæmorrhous, Gmel.

26"Hazardasitaum" the Persian name for the bulbul. "The Persians," according to Zakary ben Mohamed al Caswini, "say the bulbul has a passion for the rose, and laments and cries when he sees it pulled."—OUSELEY'S Oriental Collections, vol. i. p. 16. According to Pallas it is the true nightingale of Europe, Sylvia luscinia, which the Armenians call boulboul, and the Crim-Tartars byl-byl-i.

27Orthotomus longicauda, Gmel.

28Ploceus baya, Blyth.; P. Philippinus, Auct.

29The engraving above is taken by permission of Mr. Gould from one of his drawings for his Birds of India.

30There is another species, the C. culminatus, so called from the convexity of its bill; but though seen in the towns, it lives chiefly in the open country, and may be constantly observed wherever there are buffaloes, perched on their backs and engaged, in company with the small Minah (Acridotheres tristis), in freeing them from ticks.

31WOLF'S Life and Adventures, p. 117.

32A similar habit has been noticed in the damask Parrots of Africa (Palæornis fuscus) which daily resort at the same hour to their accustomed pools to bathe.

33Similar instances are recorded in other countries of sudden and prodigious mortality amongst crows; but whether occasioned by lightning seems uncertain. In 1839 thirty-three thousand dead crows were found on the shores of a lake in the county Westmeath in Ireland after a storm.—THOMPSON'S Nat. Hist. Ireland, vol. i. p. 319. PATTERSON in his Zoology, p. 356, mentions other cases.

34Annals of Nat. Hist. vol. xiii. p. 263.

35Treron bicincta. Jerd.

36Alsocomus puniceus, the "Season Pigeon" of Ceylon, so called from its periodical arrival and departure.

37Chalcophaps Indicus, Linn.

38Gallus Lafayetti, Lesson.

39I apprehend that in the particular of the peculiar cry the Ceylon jungle fowl differs from that of the Dekkan, where I am told that it crows like a bantam cock.

40Tantalus leucocephalus, and Ibis falcinellus.

41The violet-headed Stork (Ciconia leticocephala).

42Platalea leucorodia, Linn.

43Ardea cinerea. A. purpurea.

44Phoenicopterus roseus, Pallas.

45Nettapus coromandelianus, Gm.

46Larus brunnicephalus, Jerd.

47Dafila acuta, Linn.

48Querquedula creeca, Linn.

49Fuligula rufina, Pallas.

50Spatula clypeata, Linn.

51Sterna minuta, Linn.

52Pelicanus Philippensis, Gmel.